One of the greatest strength of your Linux distribution is its package manager and the associated software repository. With them, you have all the necessary tools and resources to download and install new software on your computer in a completely automated manner.

But despite all their efforts, the package maintainers cannot handle each and every use cases. Nor can they package all the software available out there. So there are still situations where you will have to compile and install new software by yourself. As for me, the most common reason, by far, I have to compile some software is when I need to run a very specific version, or modify the source code by the use of some fancy compilation options.

If your needs belong to the latter category, chances are you already know what to do. But, for the vast majority of Linux users, compiling and installing software from the source code for the first time might look like an initiation ceremony: somewhat frightening; but with the promise of entering a new world of possibilities and a place of prestige in a privileged community.

A. Installing software from source code in Linux

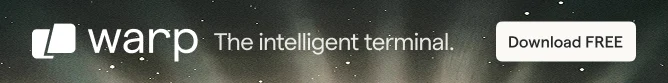

And that’s exactly what we will do here. For the purpose of this article, let’s say I need to install Node.js v8.1.1 on my system. That version exactly. A version which is not available from the Debian repository:

apt-cache madison nodejs | grep amd64

Now, installing Node.js on Ubuntu or Debian is pretty simple if you do it with the package manager. But let’s do it via the source code.

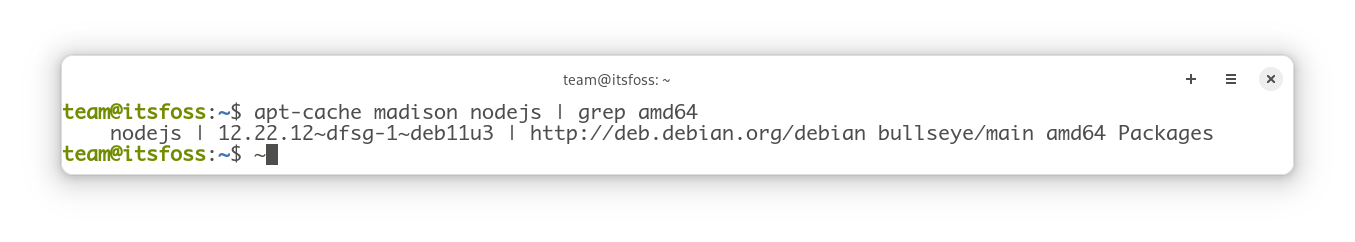

Step 1: Getting the source code from GitHub

Like many open-source projects, the sources of Node.js can be found on GitHub. So, let’s go directly there.

If you’re not familiar with GitHub, git or any other version control system worth mentioning, the repository contains the current source for the software, as well as a history of all the modifications made through the years to that software. Eventually up to the very first line written for that project. For developers, keeping that history has many advantages. For us today, the main one is we will be able to get the sources from the project as they were at any given point in time. More precisely, I will be able to get the sources as they were when the 8.1.1 version I want was released. Even if there were many modifications since then.

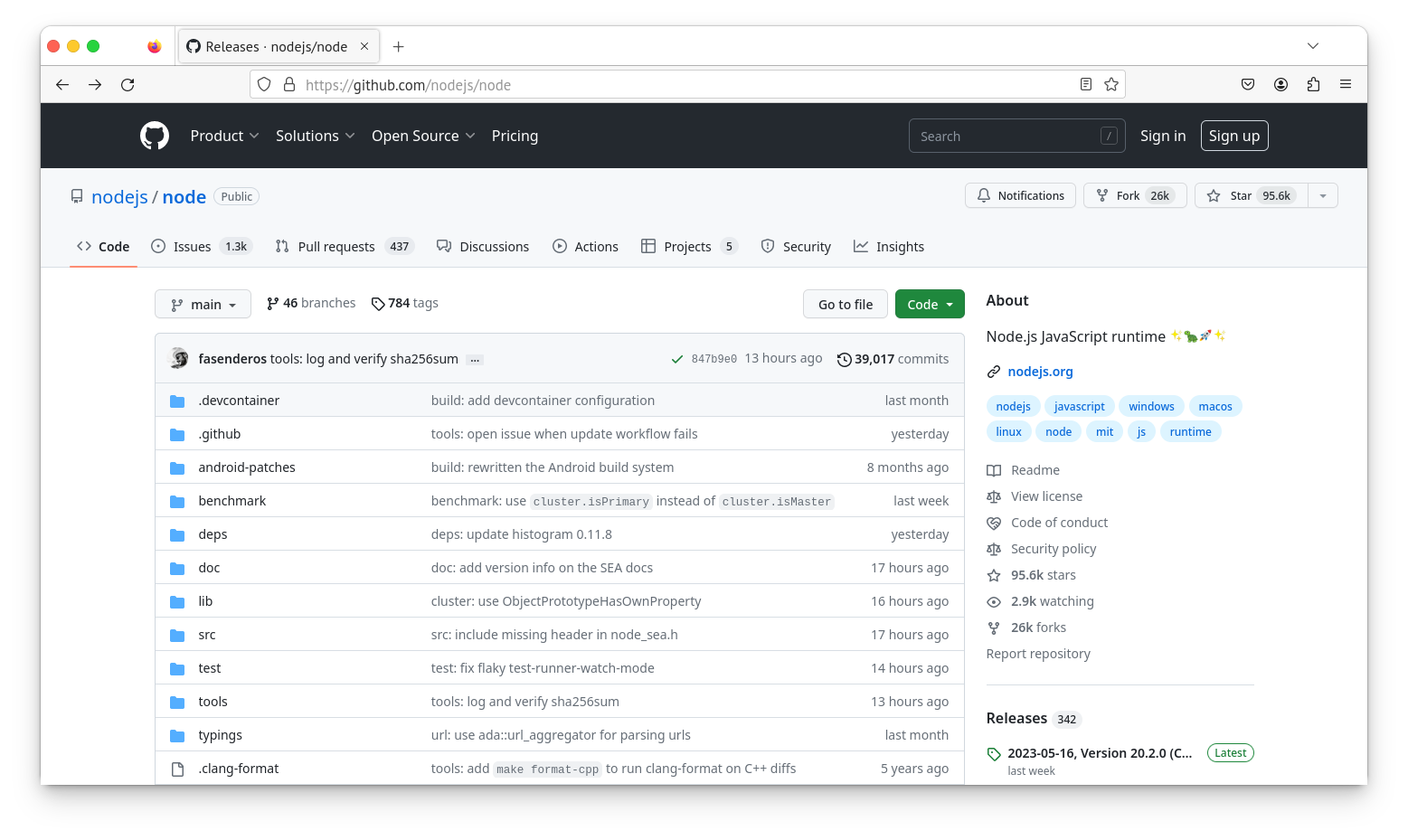

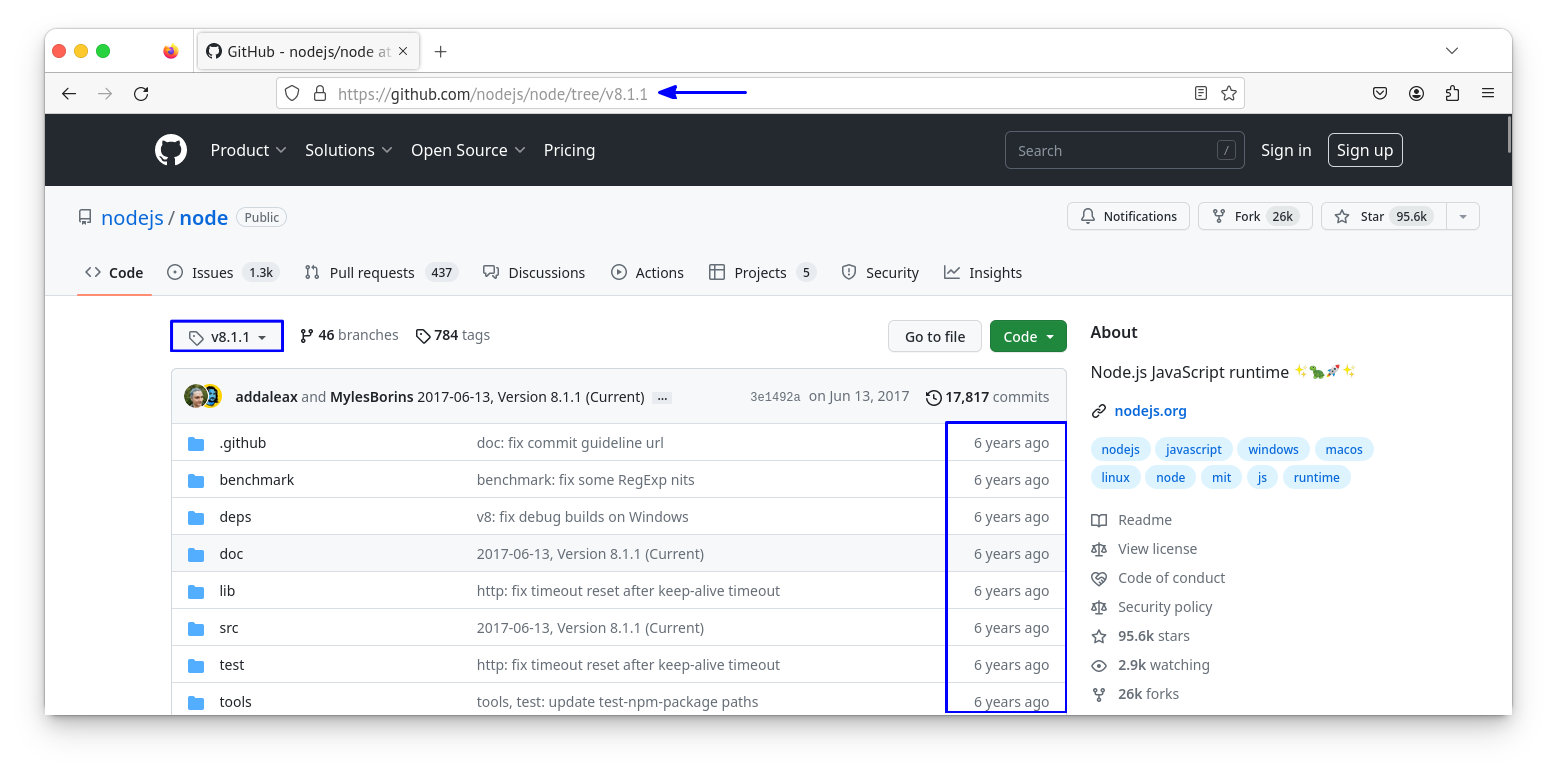

On GitHub, you can use the branch button to navigate between different versions of the software. “Branch” and “tags” are somewhat related concepts in Git. Basically, the developers create “branch” and “tags” to keep track of important events in the project history, like when they start working on a new feature or when they publish a release. I will not go into the details here, all you need to know is, I’m looking for the version tagged “v8.1.1”.

After having chosen the “v8.1.1” tag, the page is refreshed, the most obvious change being the tag now appears as part of the URL. In addition, you will notice the file change dates are different too. The source tree you are now seeing is the one that existed at the time the v8.1.1 tag was created. In some sense, you can think of a version control tool like git as a time travel machine, allowing you to go back and forth in a project history.

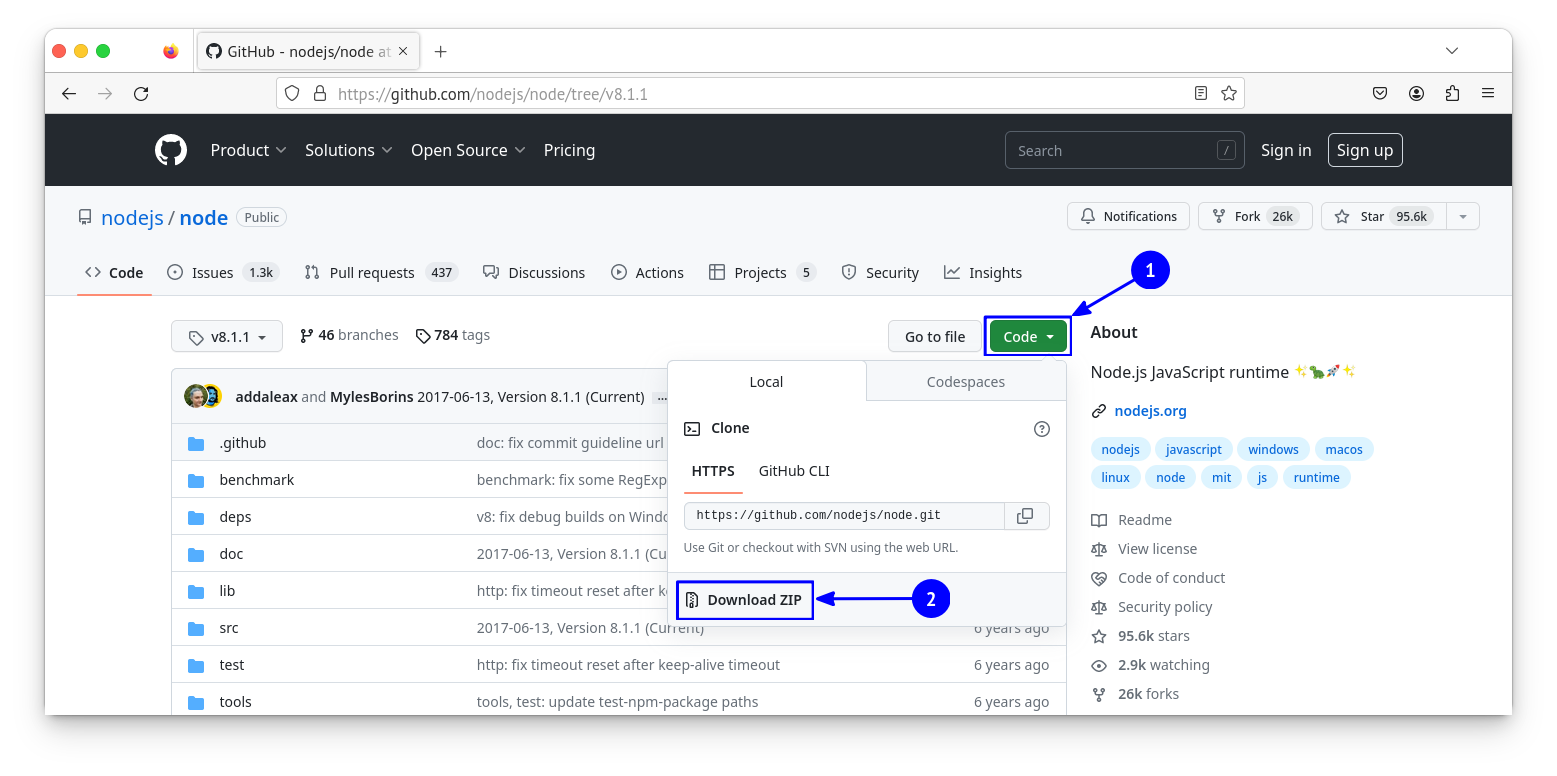

At this point, we can download the sources of Node.js 8.1.1. You can’t miss the big button suggesting downloading the ZIP archive of the project. As for me, I will download and extract the ZIP from the command line for the sake of the explanation. But if you prefer using a GUI tool, don’t hesitate to do that instead:

wget https://github.com/nodejs/node/archive/v8.1.1.zip

unzip v8.1.1.zip

cd node-8.1.1/Downloading the ZIP archive works great. But if you want to do it “like a pro”, I would recommend using directly the git tool to download the sources. It is not complicated at all — and it will be a nice first contact with a tool you will often encounter.

sudo apt install git to quickly install git.Make a shallow clone of the Node.js repository at v8.1.1

git clone --depth 1 \

--branch v8.1.1 \

https://github.com/nodejs/node

cd node/By the way, if you have an issue, just consider the first part of this article as a general introduction. Later I have more detailed explanations for Debian and Red Hat based distributions in order to help you troubleshoot common issues.

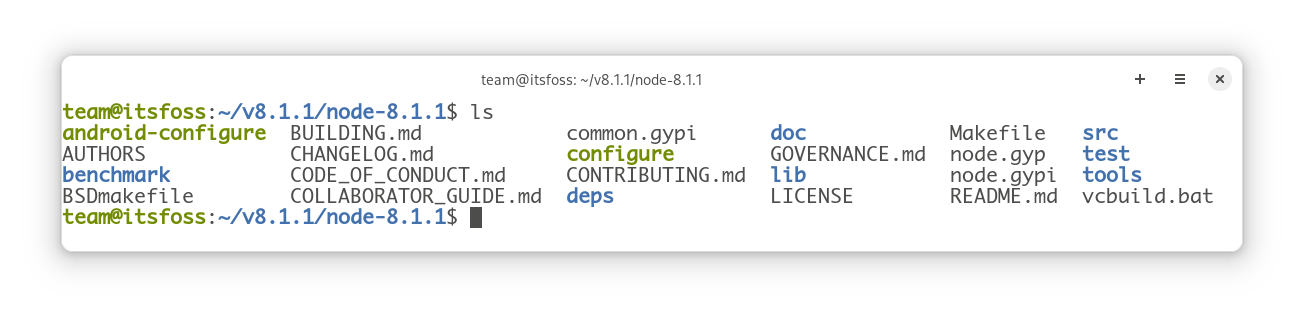

Anyway, whenever you downloaded the source using git or as a ZIP archive, you should now have exactly the same source files in the current directory:

Step 2: Understanding the Build System of the program

We usually talk about “compiling the sources”, but the compilation is only one of the phases required to produce a working software from its source. A build system is a set of tools and practices used to automate and articulate those different tasks in order to build the software entirely just by issuing a few commands.

If the concept is simple, the reality is somewhat more complicated because different projects or programming languages may have different requirements. Or because of the programmer’s tastes. Or the supported platforms. Or for historical reasons. Or… or… there is an almost endless list of reasons to choose or create another build system. All that to say, there are many solutions used out there.

Node.js uses a GNU-style build system. It is a popular choice in the open source community and, once again, a good way to start your journey.

Writing and tuning a build system is a pretty complex task, but for the “end user”, GNU-style build systems ease the task by using two tools: configure and make.

The configure file is a project-specific script that will check the destination system configuration and available features in order to ensure the project can be built, eventually dealing with the specificities of the current platform.

An important part of a typical configure job is to build the Makefile. That is the file containing the instructions required to effectively build the project.

The make tool, on the other hand, is a POSIX tool available on any Unix-like system. It will read the project-specific Makefile and perform the required operations to build and install your program.

But, as always in the Linux world, you still have some leniency in customizing the build to your specific needs.

./configure --helpThe configure -help command will show you all the available configuration options. Once again, this is very project-specific. And to be honest, it is sometimes necessary to dig into the project before fully understanding the meaning of each and every configure option.

But there is at least one standard GNU Autotools option that you must know: the --prefix option. This has to do with the file system hierarchy and the place your software will be installed.

Step 3: The FHS

The Linux file system hierarchy on a typical distribution mostly complies with the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS).

That standard explains the purpose of the various directories of your system: /usr, /tmp, /var and so on.

When using the GNU Autotools— and most other build systems— the default installation location for your new software will be /usr/local. This is a good choice because according to the FSH:

The /usr/local hierarchy somehow replicates the root directory, and you will find there /usr/local/bin for the executable programs, /usr/local/lib for the libraries, /usr/local/share for architecture-independent files and so on.

The only issue when using the /usr/local tree for custom software installation is the files for all your software will be mixed there. Especially after having installed a couple of software, it will be hard to track to which file exactly of /usr/local/bin and /usr/local/lib belongs to which software. That will not cause any issues to the system though. After all, /usr/bin is just about the same mess. But that will become an issue the day you will want to remove manually installed software.

To solve that issue, I usually prefer installing custom software in the /opt subtree instead. Once again, to quote the FHS:

/opt must locate its static files in a separate /opt/<package> or /opt/<provider> directory tree, where <package> is a name that describes the software package and <provider> is the provider’s LANANA registered name.So we will create a subdirectory of /opt specifically for our custom Node.js installation. And if someday I want to remove that software, I will simply have to remove that directory:

sudo mkdir /opt/node-v8.1.1

sudo ln -sT node-v8.1.1 /opt/node./configure --prefix=/opt/node-v8.1.1

make -j9 && echo ok-j9 means run up to 9 parallel tasks to build the software. As a rule of thumb, use -j(N+1) where N is the number of cores of your system. That will maximize the CPU usage (one task per CPU thread/core + a provision of one extra task when a process is blocked by an I/O operation).

Anything but “ok” after the make command has been completed would mean there was an error during the build process. As we ran a parallel build because of the -j option, it is not always easy to retrieve the error message given the large volume of output produced by the build system.

In the case of an issue, just restart make, but without the -j option this time. And the error should appear near the end of the output:

makeFinally, once the compilation has gone to the end, you can install your software to its location by running the command:

sudo make installAnd test it:

sh$ /opt/node/bin/node --version

v8.1.1B. What if things go wrong while installing from source code?

What I’ve explained above is mostly what you can see on the “build instruction” page of a well-documented project. But given this article's goal is to let you compile your first software from sources, it might be worth taking the time to investigate some common issues. So, I will do the whole procedure again, but this time from a fresh and minimal Debian and CentOS systems, so you can see the errors I encountered and how I solved them.

From Debian “Stretch”

itsfoss@debian:~$ git clone --depth 1 \

--branch v8.1.1 \

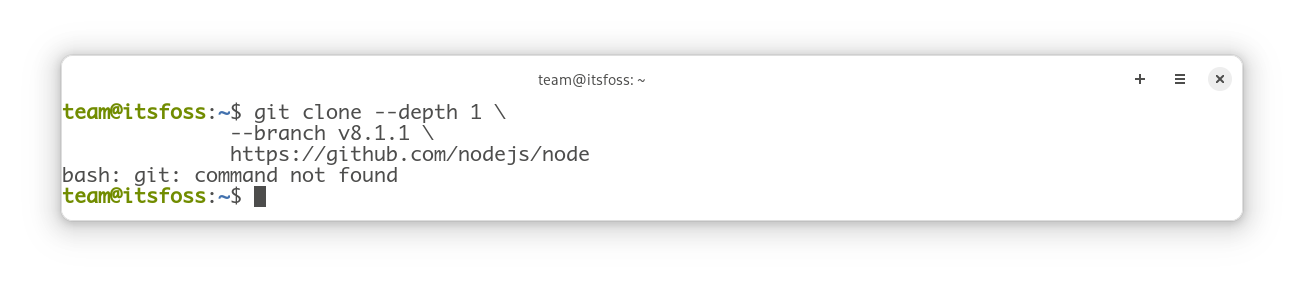

https://github.com/nodejs/nodeProblem: Git command not found

This problem is quite easy to diagnose and solve. Just install the git package:

itsfoss@debian:~$ sudo apt install git

itsfoss@debian:~$ git clone --depth 1 \

--branch v8.1.1 \

https://github.com/nodejs/node && echo ok

[...]

okitsfoss@debian:~/node$ sudo mkdir /opt/node-v8.1.1

itsfoss@debian:~/node$ sudo ln -sT node-v8.1.1 /opt/nodeNo problem here.

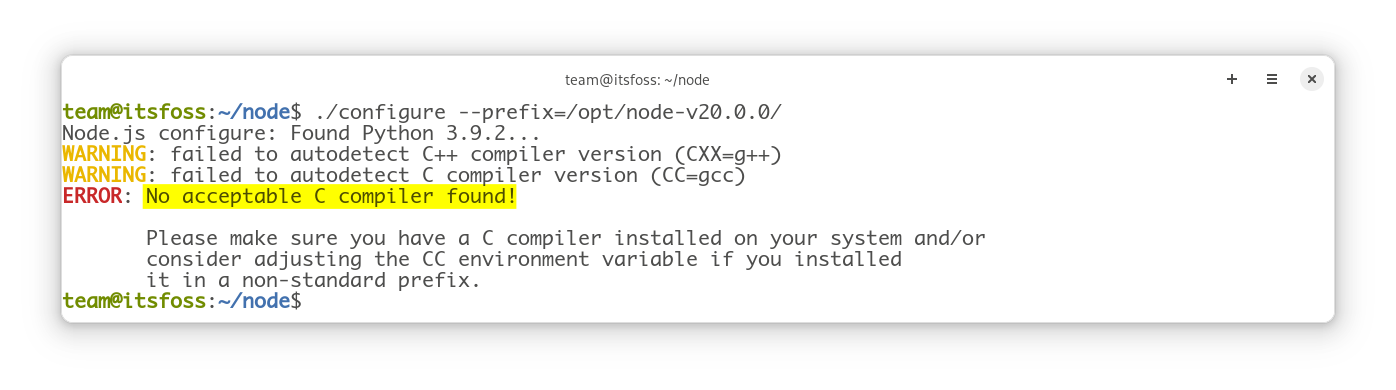

itsfoss@debian:~/node$ ./configure --prefix=/opt/node-v8.1.1/Problem: No acceptable C compiler found!

Obviously, to compile a project, you need a compiler. Node.js being written using the C++ language, we require a C++ compiler. Here I will install g++, the GNU C++ compiler for that purpose:

itsfoss@debian:~/node$ sudo apt-get install g++

itsfoss@debian:~/node$ ./configure --prefix=/opt/node-v8.1.1/ && echo ok

[...]

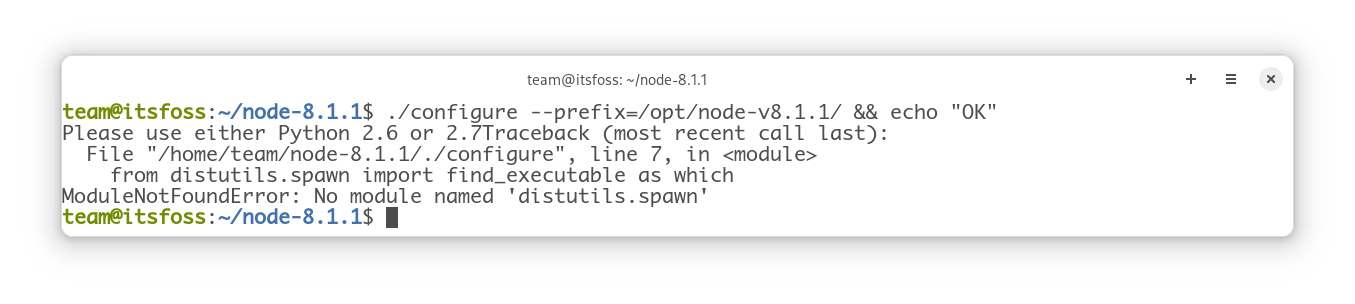

okitsfoss@debian:~/node$ make -j9 && echo okProblem: make command not found

make command not foundOne other missing tool. Same symptoms. Same solution:

itsfoss@debian:~/node$ sudo apt-get install make

itsfoss@debian:~/node$ make -j9 && echo ok

[...]

okitsfoss@debian:~/node$ sudo make install

[...]

itsfoss@debian:~/node$ /opt/node/bin/node --version

v8.1.1Success!

From CentOS

[itsfoss@centos ~]$ git clone --depth 1 \

--branch v8.1.1 \

https://github.com/nodejs/node

-bash: git: command not foundCommand not found? Just install it using the yum package manager:

[itsfoss@centos ~]$ sudo yum install git

[itsfoss@centos ~]$ git clone --depth 1 \

--branch v8.1.1 \

https://github.com/nodejs/node && echo ok

[...]

ok[itsfoss@centos ~]$ sudo mkdir /opt/node-v8.1.1

[itsfoss@centos ~]$ sudo ln -sT node-v8.1.1 /opt/node[itsfoss@centos ~]$ cd node

[itsfoss@centos node]$ ./configure --prefix=/opt/node-v8.1.1/

WARNING: failed to autodetect C++ compiler version (CXX=g++)

WARNING: failed to autodetect C compiler version (CC=gcc)

Node.js configure error: No acceptable C compiler found!

Please make sure you have a C compiler installed on your system and/or

consider adjusting the CC environment variable if you installed

it in a non-standard prefix.You guess it: NodeJS is written using the C++ language, but my system lacks the corresponding compiler. Yum to the rescue. As I’m not a regular CentOS user, I actually had to search on the Internet the exact name of the package containing the g++ compiler.

Leading me to that page: https://superuser.com/questions/590808/yum-install-gcc-g-doesnt-work-anymore-in-centos-6-4

[itsfoss@centos node]$ sudo yum install gcc-c++

[itsfoss@centos node]$ ./configure --prefix=/opt/node-v8.1.1/ && echo ok

[...]

ok[itsfoss@centos node]$ make -j9 && echo ok

[...]

ok[itsfoss@centos node]$ sudo make install && echo ok

[...]

ok[itsfoss@centos node]$ /opt/node/bin/node --version

v8.1.1Success again!

C. Making changes to the software installed from source code

You may install software from the source because you need a very specific version not available in your distribution repository or because you want to modify the program to fix a bug or add a feature. After all, open-source is all about making modifications. So, I will take this opportunity to give you a taste of the power you have at hand now that you are able to compile your own software.

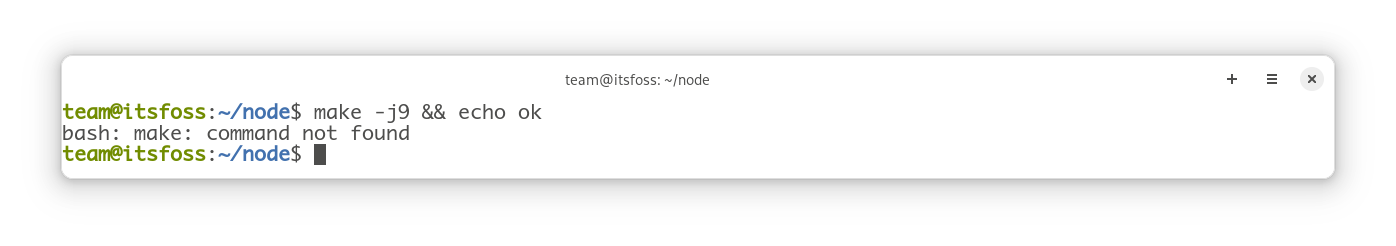

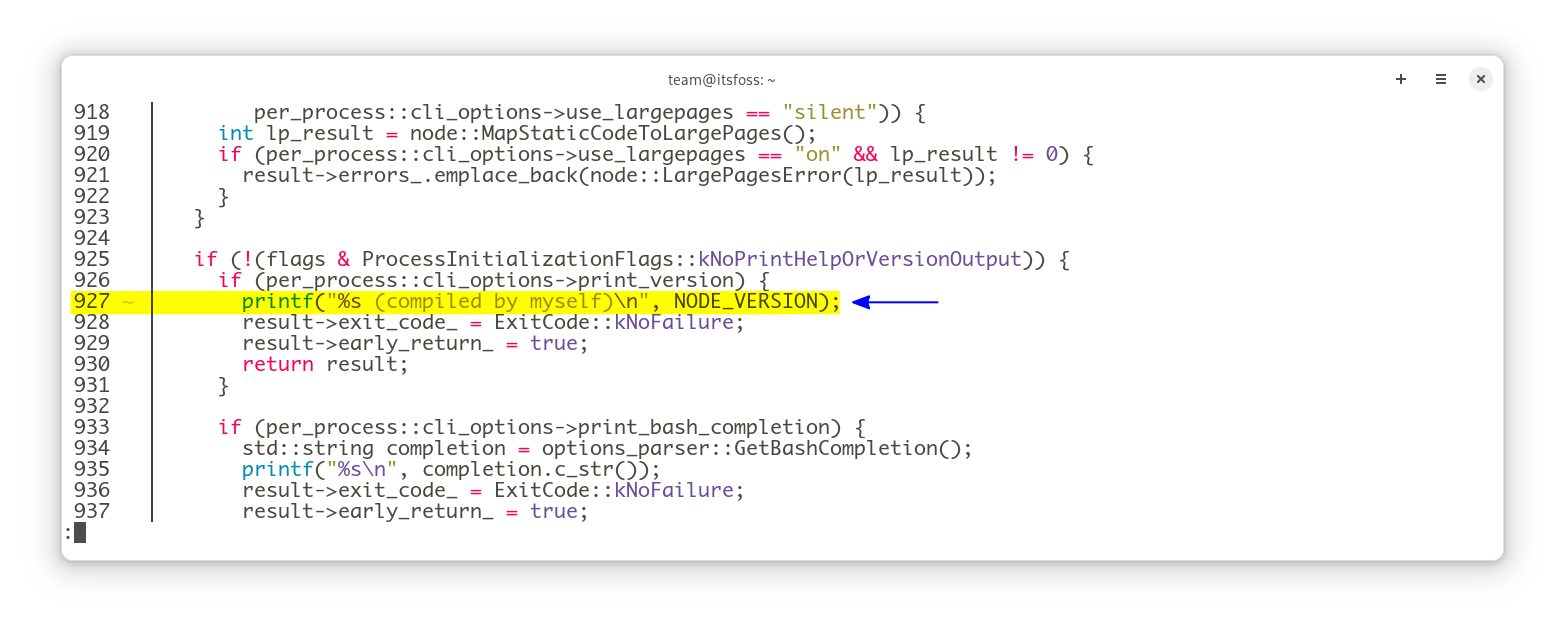

Here, we will make a minor change to the sources of Node.js. And we will see if our change will be incorporated into the compiled version of the software:

Open the file node/src/node.cc in your favorite text editor (vim, nano, gedit, … ). And try to locate that fragment of code:

if (debug_options.ParseOption(argv[0], arg)) {

// Done, consumed by DebugOptions::ParseOption().

} else if (strcmp(arg, "--version") == 0 || strcmp(arg, "-v") == 0) {

printf("%s\n", NODE_VERSION);

exit(0);

} else if (strcmp(arg, "--help") == 0 || strcmp(arg, "-h") == 0) {

PrintHelp();

exit(0);

}

It is around line 3830 of the file in v8.1.1. Then modify the line containing printf to match that one instead:

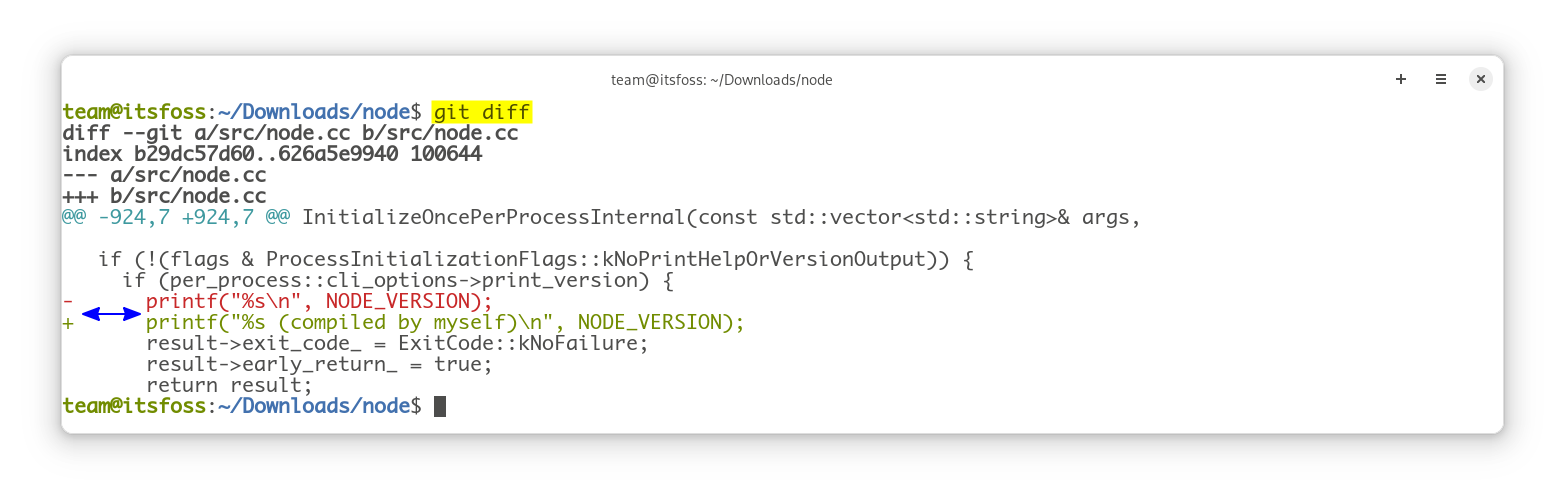

printf("%s (compiled by myself)\n", NODE_VERSION);Then head back to your terminal. Before going further— and to give you some more insight of the power behind git— you can check if you’ve modified the right file:

git diff

git diff commandYou should see a “-” (minus sign) before the line as it was before you changed it. And a “+” (plus sign) before the line after your changes.

It is now time to recompile and re-install your software:

make -j9 && sudo make install && echo ok

[...]

okThis times, the only reason it might fail is that you’ve made a typo while changing the code. If this is the case, re-open the node/src/node.cc file in your text editor and fix the mistake.

Once you’ve managed to compile and install that new modified NodeJS version, you will be able to check if your modifications were actually incorporated into the software:

itsfoss@debian:~/node$ /opt/node/bin/node --version

v8.1.1 (compiled by myself)Congratulations! You’ve made your first change to an open-source program!

D. Let the shell locate our custom build software

You may have noticed that I’ve always launched my newly compiled NodeJS software by specifying the absolute path to the binary file.

/opt/node/bin/nodeIt works. But this is annoying, to say the least.

There are actually two common ways of fixing the annoying problem of specifying the absolute path to the binary files, but to understand them you must first know that your shell locates the executable files by looking for them only in the directories specified by the PATH environment variable.

itsfoss@debian:~/node$ echo $PATH

/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/local/games:/usr/gamesHere, on that Debian system, if you do not specify explicitly any directory as part of a command name, the shell will first look for the executable programs in /usr/local/bin, then if not found into /usr/bin, then if not found into /bin then if not found into /usr/local/games then if not found into /usr/games, then if not found … the shell will report an error “command not found”.

Given that, we have two way to make a command accessible to the shell: by adding it to one of the already configured PATH directories. Or by adding the directory containing our executable file to the PATH.

Adding a link from /usr/local/bin

Just copying the node binary executable from /opt/node/bin to /usr/local/bin would be a bad idea since by doing so, the executable program would no longer be able to locate the other required components belonging to /opt/node/ (it’s a common practice for software to locate its resource files relative to its own location).

So, the traditional way of doing that is by using a symbolic link:

itsfoss@debian:~/node$ sudo ln -sT /opt/node/bin/node /usr/local/bin/node

itsfoss@debian:~/node$ which -a node || echo not found

/usr/local/bin/node

itsfoss@debian:~/node$ node --version

v8.1.1 (compiled by myself)This is a simple and effective solution, especially if a software package is made of just few well known executable programs— since you have to create a symbolic link for each and every user-invokable command. For example, if you’re familiar with NodeJS, you know the npm companion application I should symlink from /usr/local/bin too. But I let that to you as an exercise.

Modifying the PATH

First, if you tried the preceding solution, remove the node symbolic link created previously to start from a clear state:

itsfoss@debian:~/node$ sudo rm /usr/local/bin/node

itsfoss@debian:~/node$ which -a node || echo not found

not foundAnd now, here is the magic command to change your PATH:

itsfoss@debian:~/node$ export PATH="/opt/node/bin:${PATH}"

itsfoss@debian:~/node$ echo $PATH

/opt/node/bin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/local/games:/usr/gamesSimply said, I replaced the content of the PATH environment variable by its previous content, but prefixed by /opt/node/bin. So, as you can imagine it now, the shell will look first into the /opt/node/bin directory for executable programs. We can confirm that using the which command:

itsfoss@debian:~/node$ which -a node || echo not found

/opt/node/bin/node

itsfoss@debian:~/node$ node --version

v8.1.1 (compiled by myself)Whereas the “link” solution is permanent as soon as you’ve created the symbolic link into /usr/local/bin, the PATH change is effective only into the current shell. I will leave you to do some research on how to make changes in the PATH permanents. As a hint, it has to do with your “profile”. If you find the solution, don’t hesitate to share that with the other readers by using the comment section below!

E. How to remove that newly installed software from source code

Since our custom compiled NodeJS software sits completely in the /opt/node-v8.1.1 directory, removing that software requires no more effort than using the rm command to remove that directory:

sudo rm -rf /opt/node-v8.1.1sudo and rm -rf are a dangerous cocktail! Always check your command twice before pressing the “enter” key. You won’t have any confirmation message and no undelete if you remove the wrong directory…Then, if you’ve modified your PATH, you will have to revert those changes, which is not complicated at all.

And if you’ve created links from /usr/local/bin you will have to remove them all:

itsfoss@debian:~/node$ sudo find /usr/local/bin \

-type l \

-ilname "/opt/node/*" \

-print -delete

/usr/local/bin/nodeWait? Where was the Dependency Hell?

As a final comment, if you read about compiling your own custom software, you might have heard about the dependency hell. This is a nickname for that annoying situation where before being able to successfully compile a software, you must first compile a pre-requisite library, which in its turn requires another library that might, in its turn, be incompatible with some other software you’ve already installed.

Part of the job of the package maintainers of your distribution is to actually resolve that dependency hell and to ensure the various software of your system are using compatible libraries and are installed in the right order.

For this article, I chose, on purpose, to install NodeJS as it virtually doesn’t have dependencies. I said “virtually” because, in fact, it has dependencies. But the source code of those dependencies are present in the source repository of the project (in the node/deps subdirectory), so you don’t have to download and install them manually beforehand.

But if you’re interested in understanding more about that problem and learning how to deal with it, let me know in the comment section below: that would be a great topic for a more advanced article!

It's FOSS turns 13! 13 years of helping people use Linux ❤️

And we need your help to go on for 13 more years. Support us with a Plus membership and enjoy an ad-free reading experience and get a Linux eBook for free.

To celebrate 13 years of It's FOSS, we have a lifetime membership option with reduced pricing of just $76. This is valid until 25th June only.

If you ever wanted to appreciate our work with Plus membership but didn't like the recurring subscription, this is your chance 😃