I have switched to Linux Mint Cinnamon, and at this point, it’s hard for me to imagine using any other OS.

I have already told you about things I like in Linux Mint. In this article, I hope to further explain why Linux Mint has become my go-to operating system.

Since I stumbled onto Mint while distro-hopping, I thought it best to present a few of Mint’s “deep” features in the same order I first encountered them.

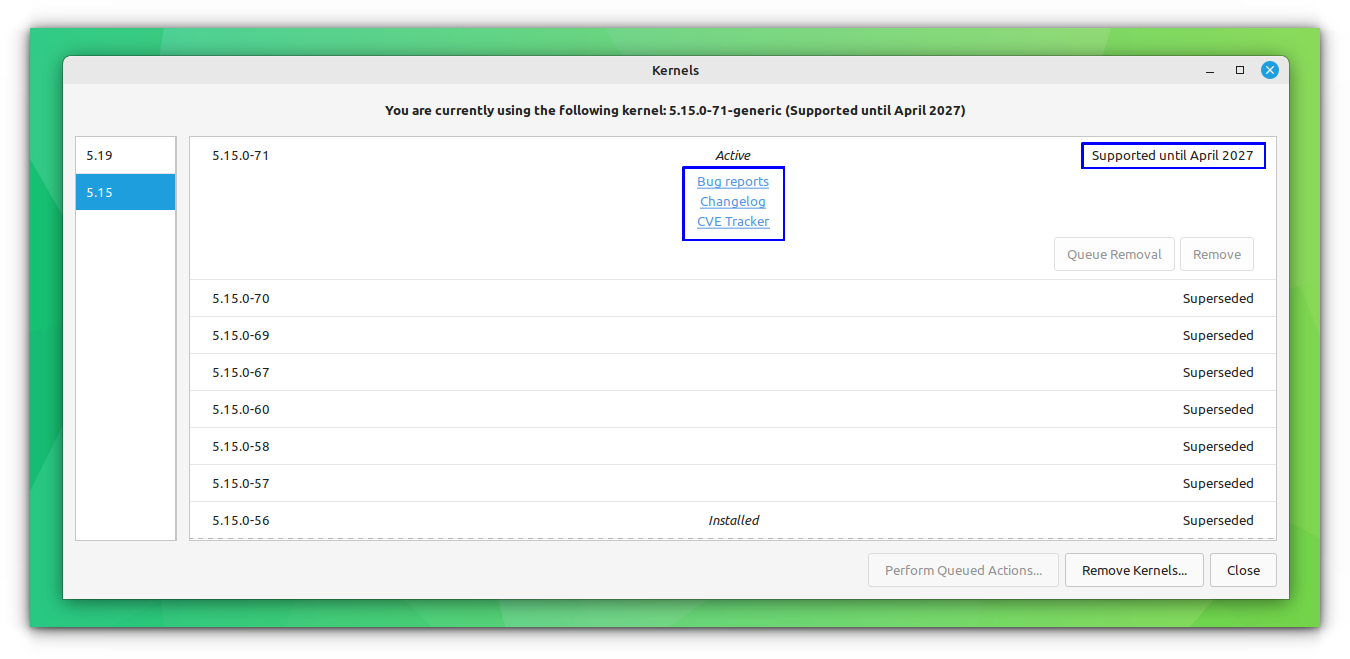

1. Update Manager: Setting your own update policy

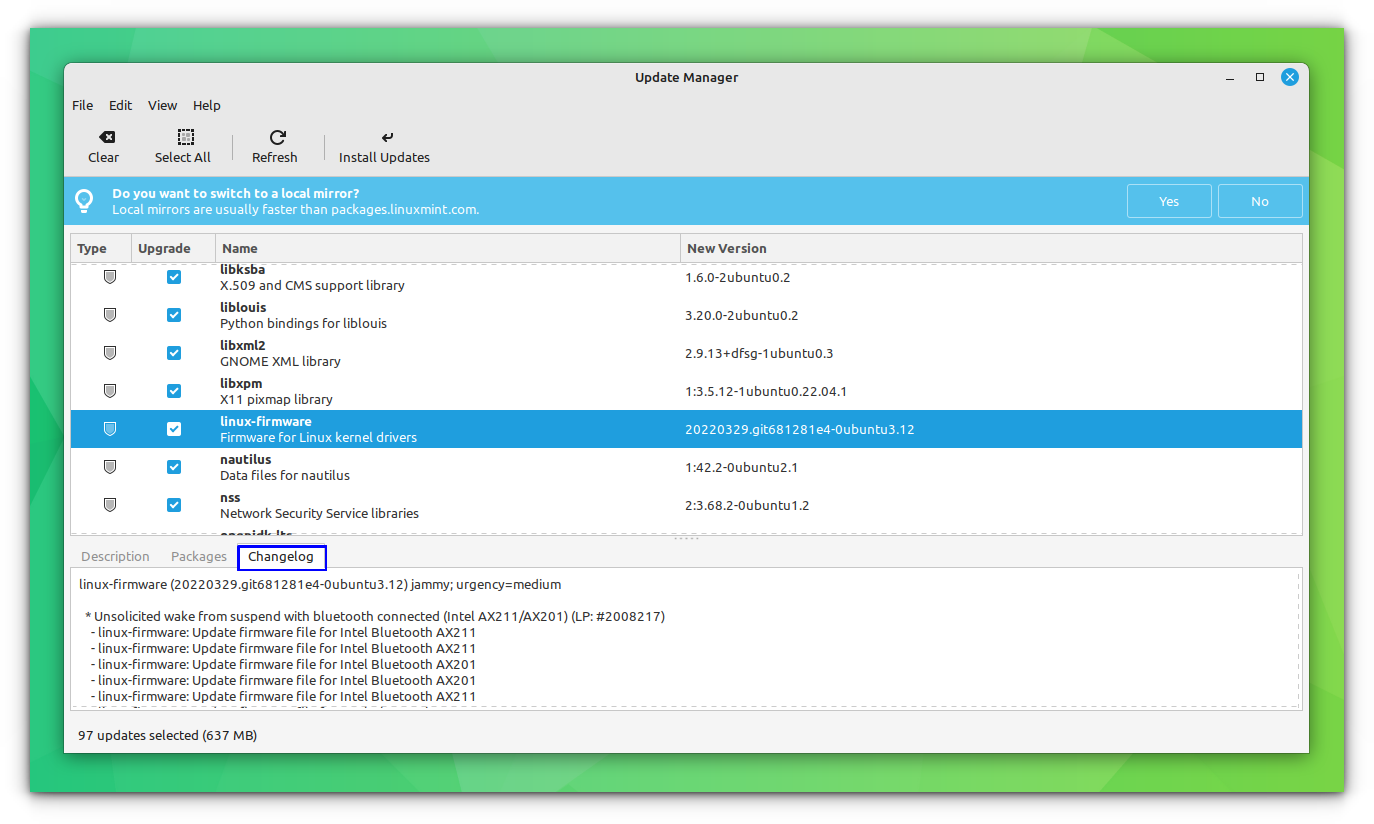

As any veteran distro-hopper can tell you, the first boot of a new OS only puts you sort of near to almost having a finished OS. The next step is to overwrite almost everything the installer just wrote on your drive and replace it with both the latest versions and with versions that most closely match your hardware configuration. So shortly after the first boot, most distros will then open their updater and display a long list of updates.

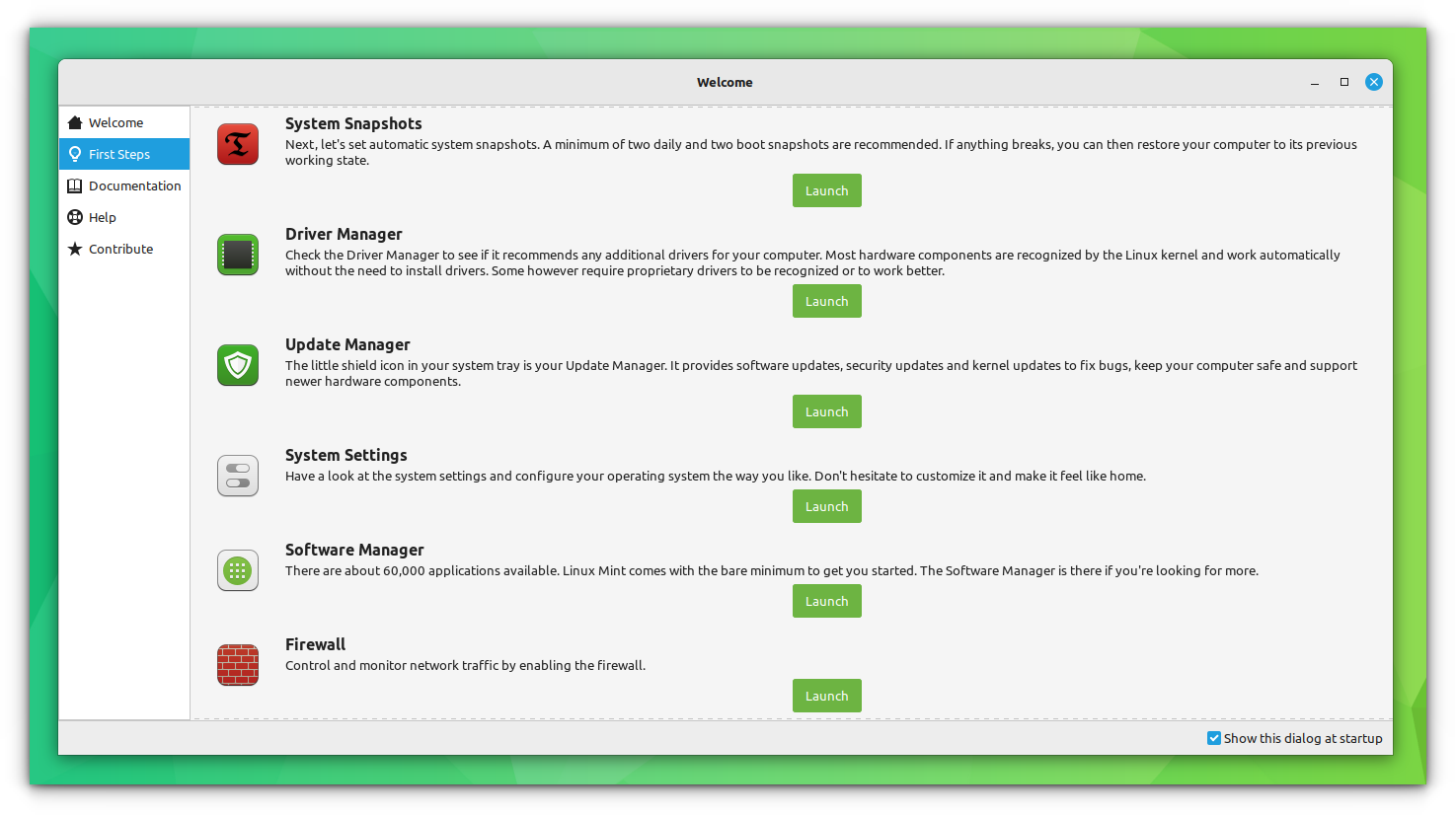

Quickly we see that Mint separates itself from the pack because in Mint we’re first asked to set a backup to your system. And it’s worthwhile to stop and consider how clever this is. By choosing to create a snapshot of your system at the beginning, you are making sure that, any updates/upgrades in the future won’t create a headache for you.

As you can see, I chose to have a snapshot in hand, ready for any unpleasant incidents. I was still smarting from a kernel regression a year earlier which had knocked out my Wi-Fi and Ethernet. Bad kernels can be removed very easily if you have a decent system backup, and especially easily if you use Timeshift.

But Mint doesn’t stop there. Click on “View” and then “Linux kernels” in the Update Manager, and a window opens allowing you to view your Linux kernel history, and allowing you to view Bug reports and the CVE tracker on yet to be installed kernels. Further, it also allows you to remove or install particular kernels.

Of course, none of this prevents you from installing a bad kernel, but it does give experienced users a solid framework to avoid kernels which might be.

A final feature is that when updates appear, you are provided with a full description, including any additions deletions or alterations to your libraries. The same feature also allows you to read the changelogs as well.

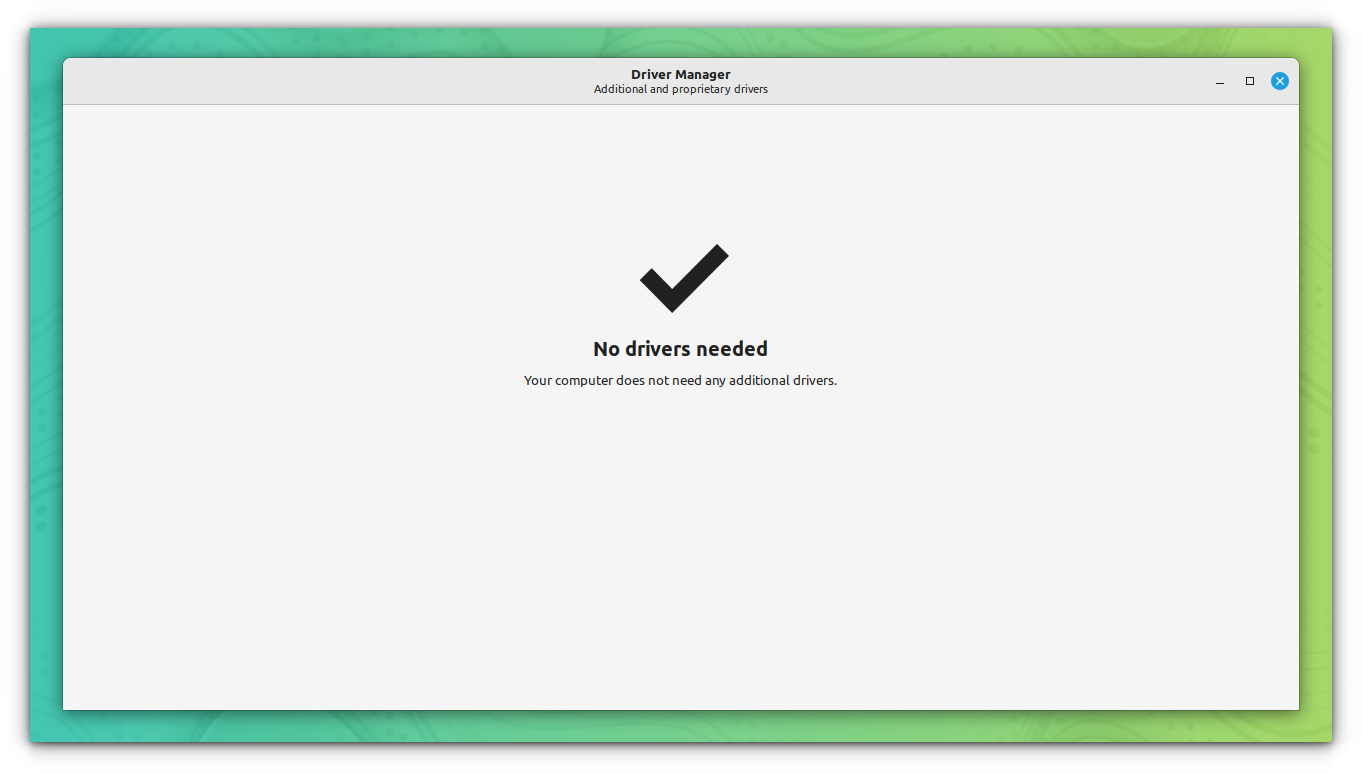

There is a Driver Manager tool, that helps you find and install necessary drivers for your system.

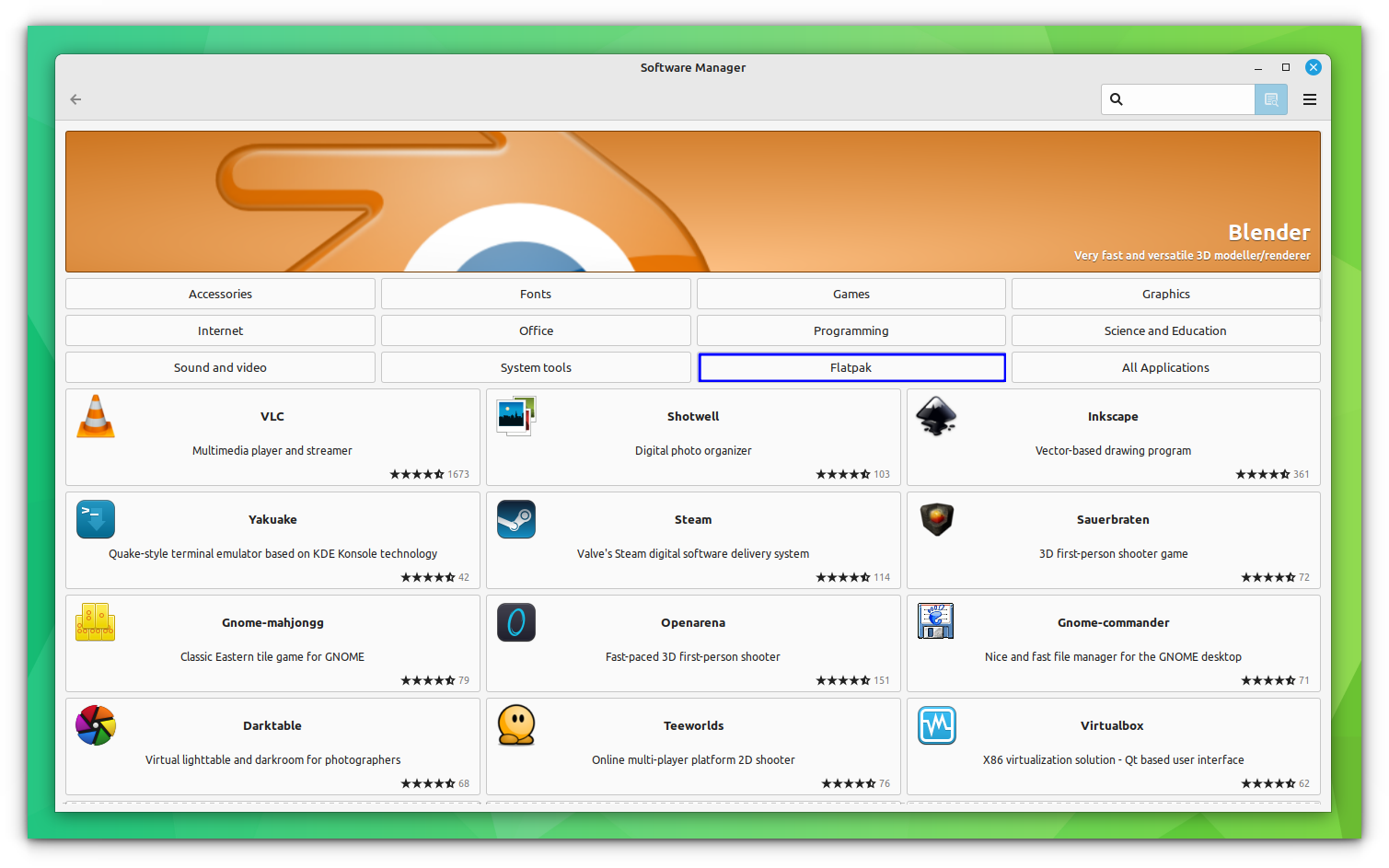

2. Software Manager: An ever-improving tool

Now that you’ve booted up Linux Mint Cinnamon for the second time, and In a certain sense the first time as a full-blown system, it’s usually time to add all the applications big and small, that make your computing environment perfect. For me, this is easy because Mint comes with most of my go-to applications already installed.

Further, I’ve never had any trouble installing applications on Linux. If they aren’t in the official repositories, I can add PPAs either in the terminal or by downloading and letting Package Manager install .deb packages. In fact, I don’t even bother checking if the distro’s repositories have “Grub Customizer”: I simply enter three commands into the terminal and 2 minutes later I’m using it.

But more timid users—users who would prefer to use a graphical software manager at all times - are in for a treat. Mint has expanded the number of available programs along with successively tweaking both its appearance and functionality. I noticed, as a single example, that with the latest releases, Mint now includes an ever-growing “Flatpak” section as well.

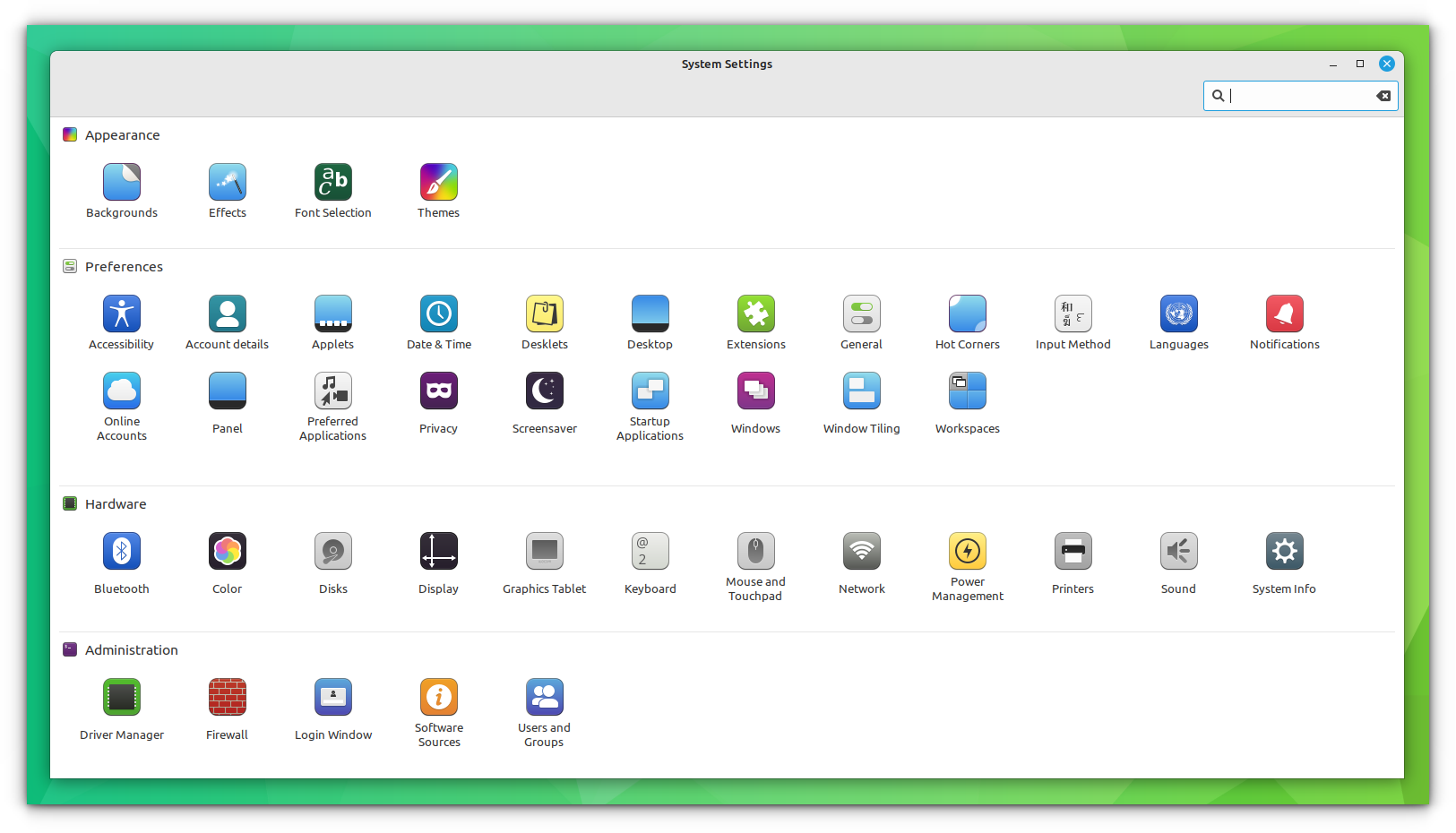

3. System Settings: Your Customization Central

The next and usually final thing a self-respecting distro-hopper does is to attempt to bend the desktop to their will. We want our new OS to look and behave in accordance with our preferences even when we’re being dumb—rather than being forced to live with someone else’s dumb ideas. For me, switching from “double click” to “single click” is my first priority. So far as I’m concerned, the failure of a distro to provide this option is grounds for dismissing it outright.

(If I live to be 1,000 I’ll never understand the double click. Is our OS so busy pursuing such a hyperactive inner life that the first click is meant as a polite tap on the shoulder? Or is it like a practice swing in golf, so that when we click a second time—the click that really matters—our click will be in absolute top-top form? And if a left click has to be done twice, why do right clicks only have to be done once? Why does the OS trust a right click but treat a left click with extreme skepticism? Is there lateral bigotry at work here? I find the issue baffling, and if anyone can come up with a good reason for it, I wish they’d tell me. Whew, I fell so much better now!)

Eventually, however, we all get around to appearance. Some distros are gorgeous. Does anyone still remember Ultimate Edition, for example? If not, consider the current version of Elementary OS. It’s so beautiful, you almost fear touching it. I fell the same about every version of Zorin I’ve used.

Linux Mint, however, is different. To be charitable, let’s simply say that Mint invites a high degree of customization.

As all distro-hoppers know, we next need to open the System Settings menu. The first thing that struck me on opening Mint’s for the first time was its sheer size in comparison to every other Linux distro I’ve seen.

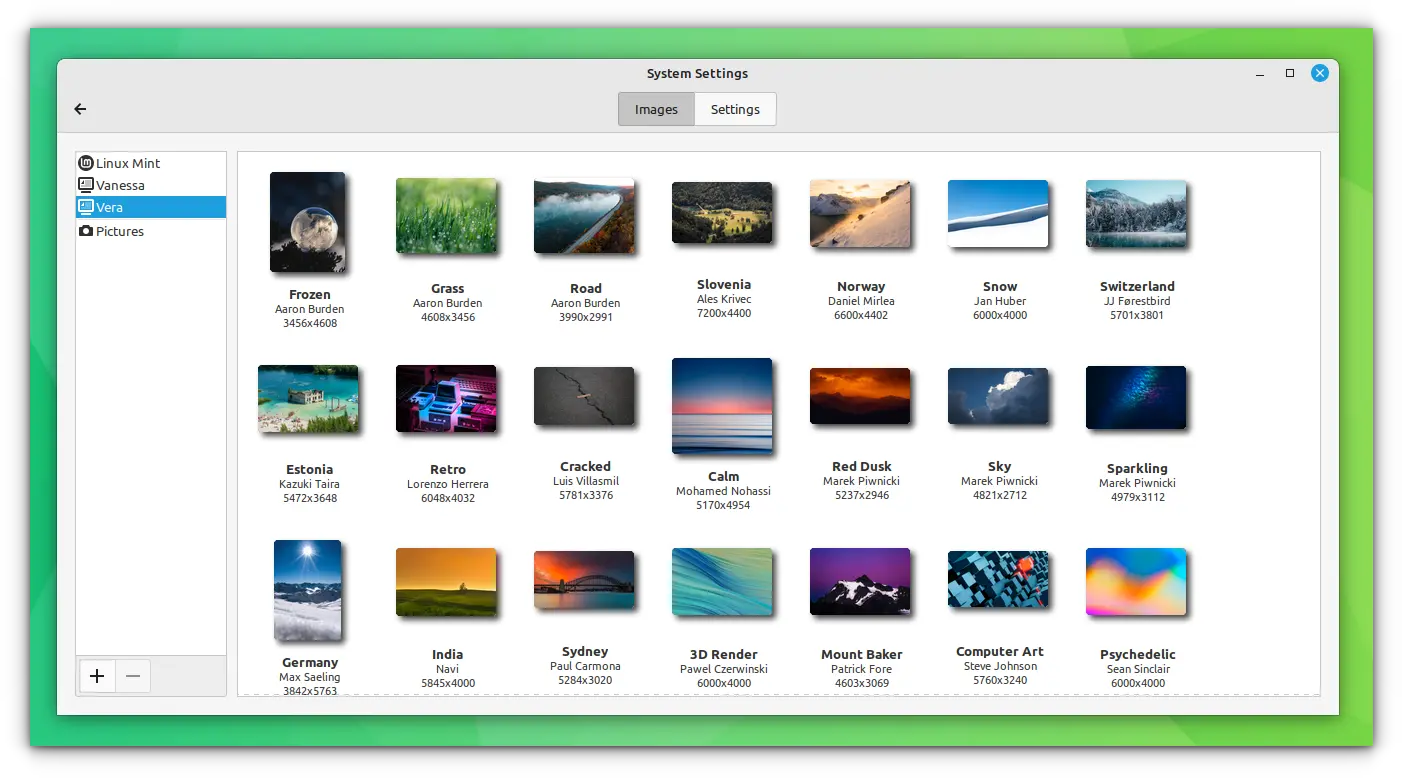

And the place we usually start is with replacing the wallpaper. As with all Linux systems, right-clicking on any photo file offers an option to set it as your background. But with Mint, you are given several version-specific sets of photos to choose from. And if none appeal to you, you can create your own sets and add them to Mint’s roster.

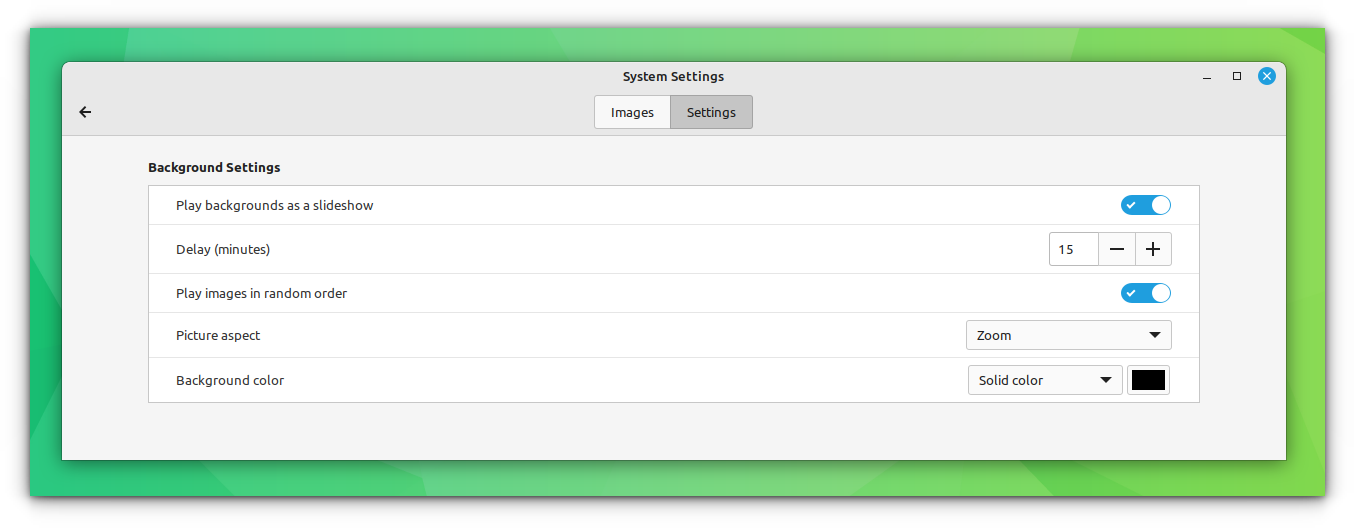

The reason I mention sets of photos is that under “settings” you can toggle the desktop slideshow feature on. The system will default to the source folder that holds your current background, and will then cycle through the entire folder either—in order or at random—and at intervals of your choosing.

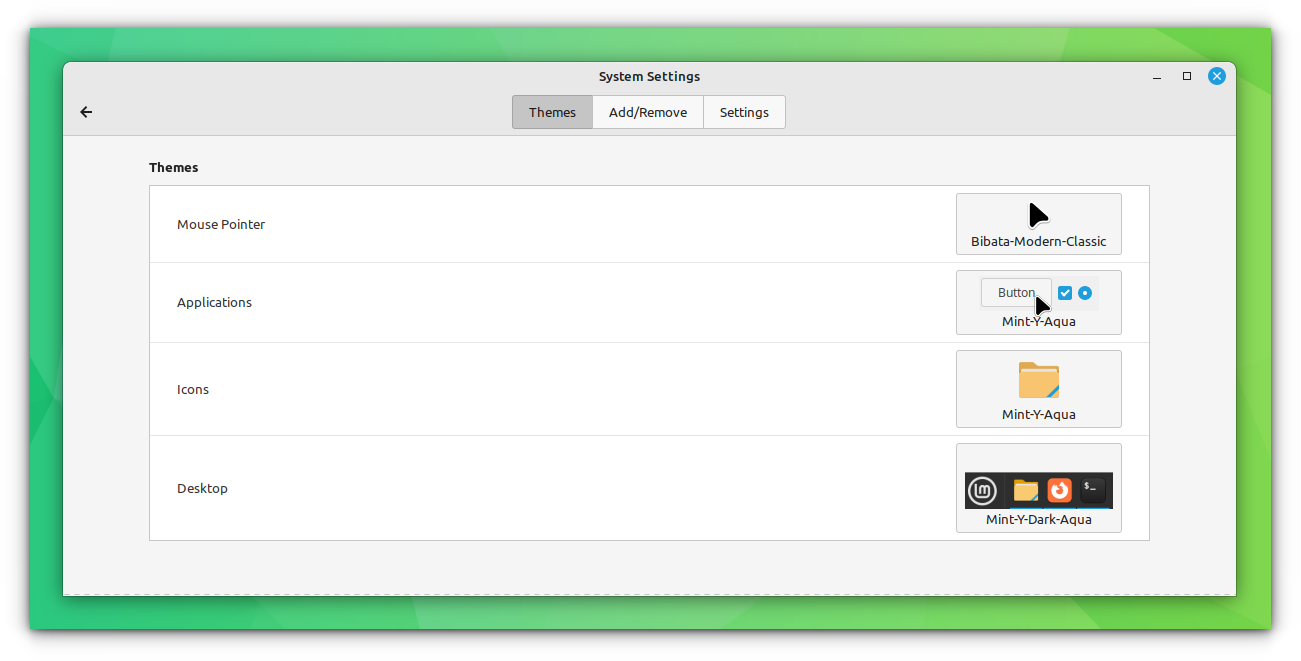

But probably the most pleasant surprise for me when I booted up Mint for the second time was opening the “Themes” tab. Instead of being able to adjust some elements to some degree, Mint places everything in front of you and allows you to easily and independently make many changes.

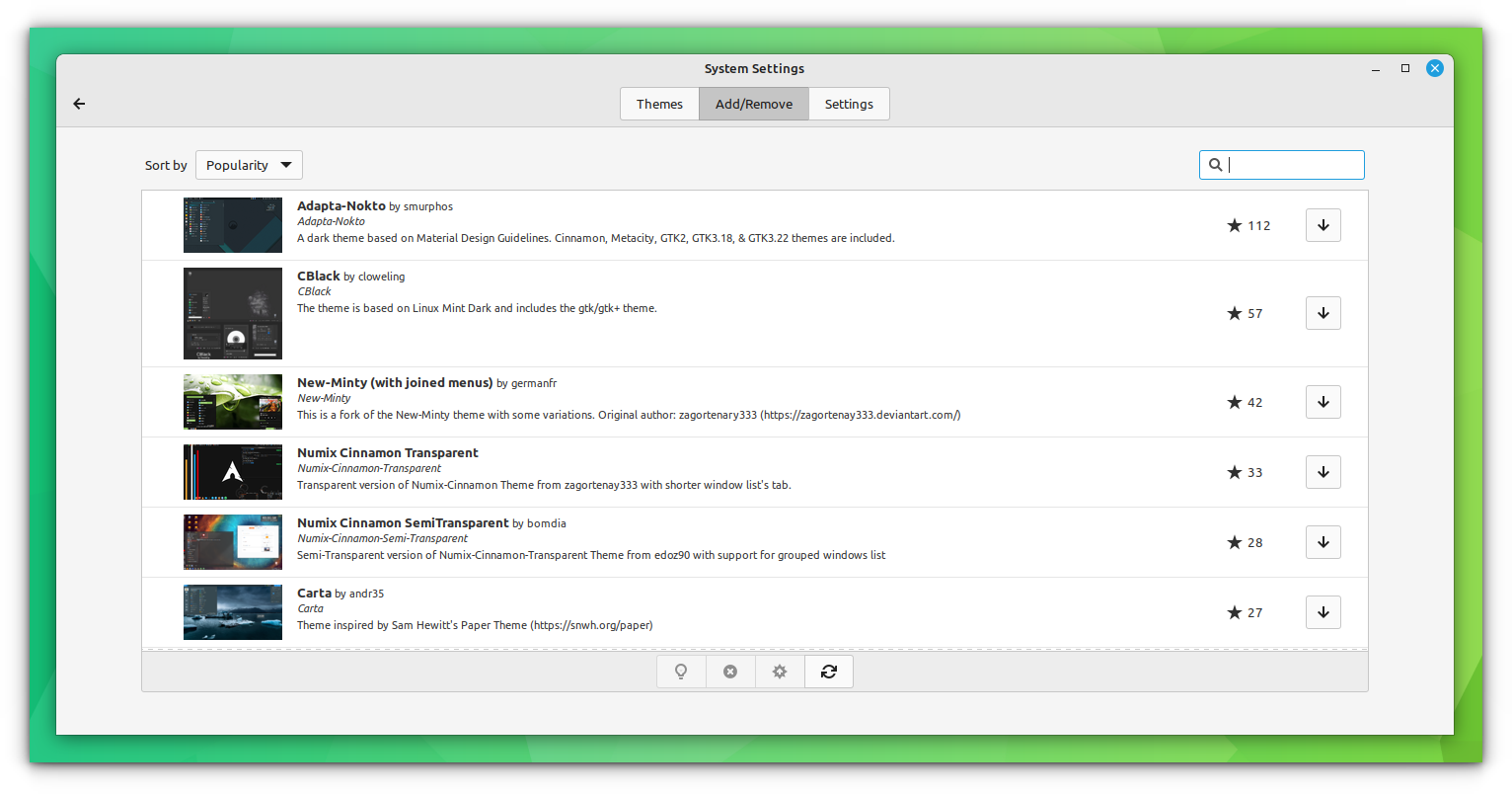

At this point, each section is already populated with a wide selection. But using the “Add/Remove” feature allows you to download, install and use scores of alternative desktop designs. Most of these give alternative looks to the panel, the main menu and panel sub-menus. Some themes are larger and come with their own “controls” and “windows borders” designs as well. These elements are then made independently available, so for example, I can apply the “Zorin 8-Black” window border to the “Glass-Glaucous” panel theme.

None of these adjustments will make the Cinnamon desktop look or act like a Mac. Or Unity or Gnome or KDE for that matter. Though I’ve never seen a mission statement on this point from Linux Mint Cinnamon, they obviously seem to be about offering a maximally Windows-like environment (Which explains why so many of the alternate desktop themes are Windows related.) I think this design strategy makes Linux Mint Cinnamon the perfect landing spot for users fleeing Microsoft. The familiarity of its look and behavior will certainly flatten the learning curve.

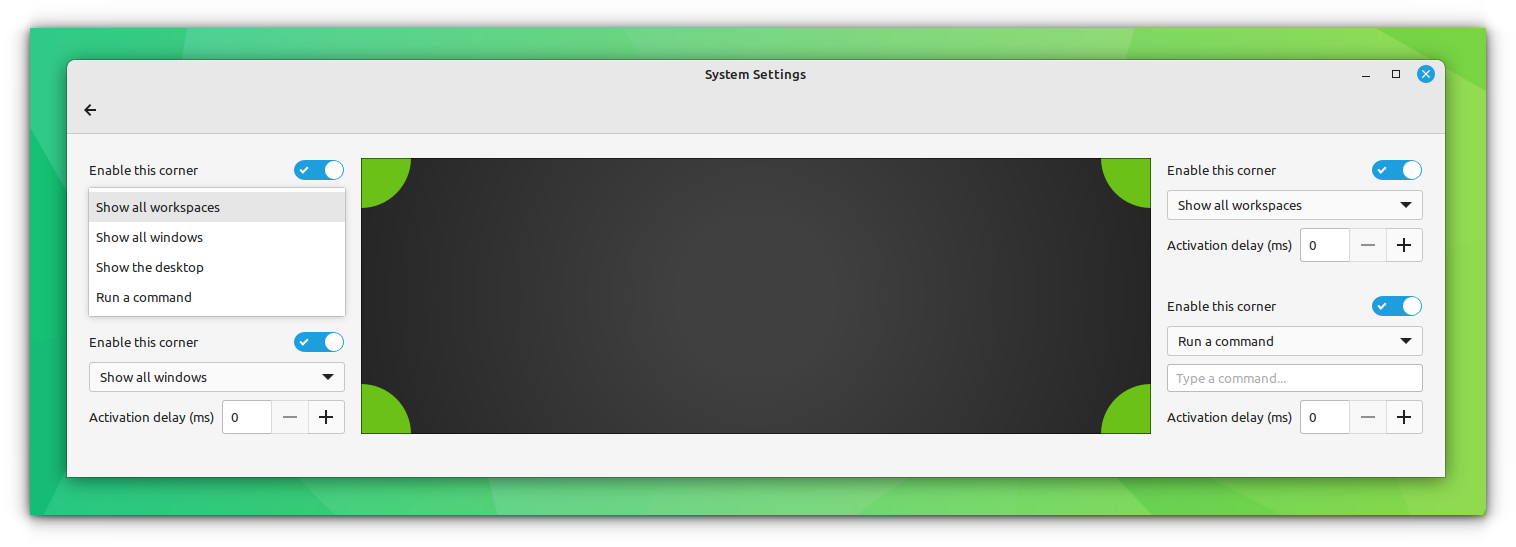

Bonus tool: Hot Corners: An elegant alternative to Desk Cube

Normally once we’ve personalized the desktop there’s not much left to do but use it. Really, with every other distro I’ve used, this is as far as you can go. But subsequent poking around revealed to me a wealth of other things waiting in the weeds. I discussed the flexibility of Mint’s sound scripts in an earlier article. But the final feature I’d like to discuss here is called “Hot Corners”.

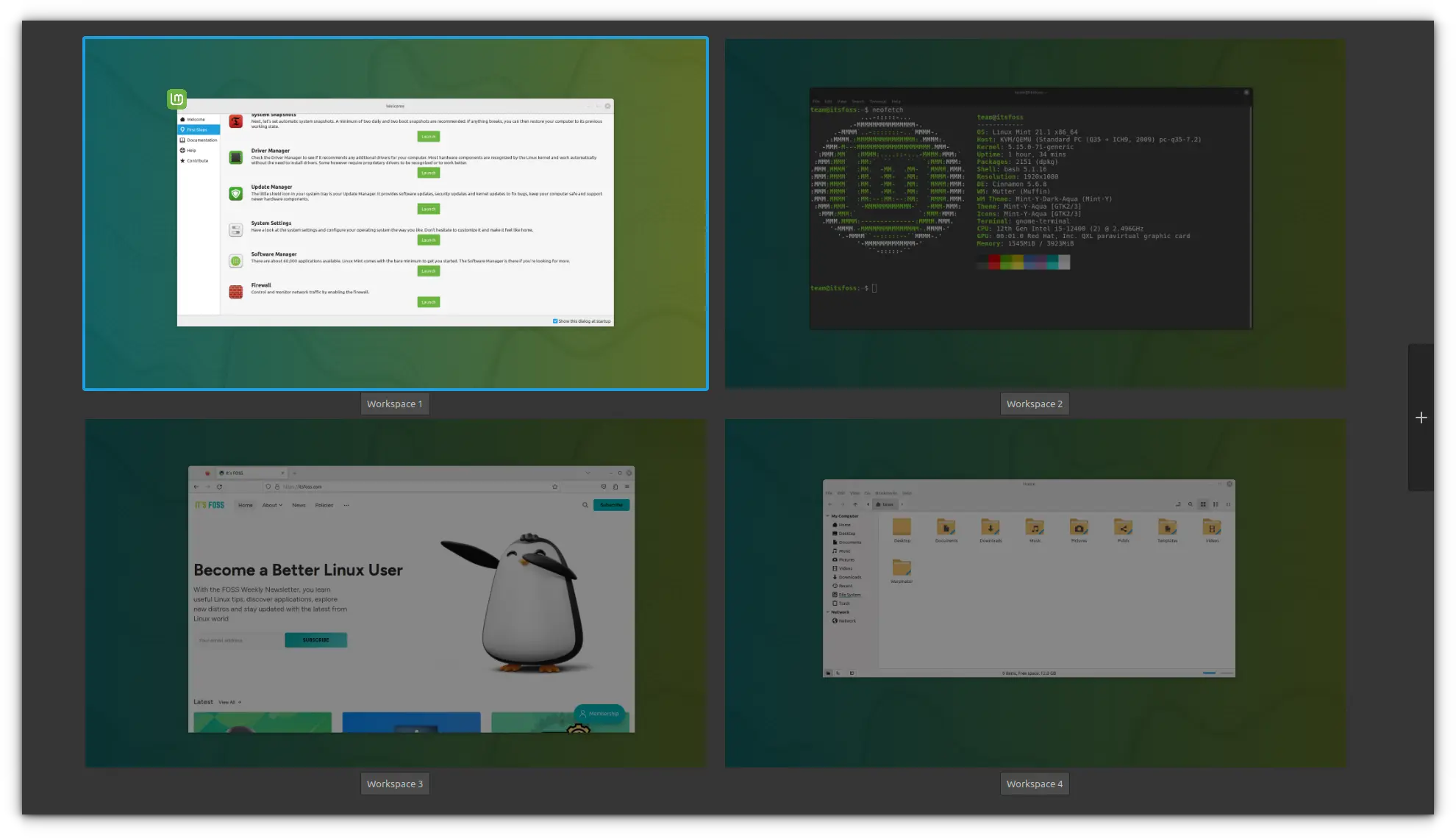

Based, I’d guess, on the same digital foundation as the Gnome activities dash, Mint has added features to it so that it can, among other things, be made to act as an elegant workplace switcher and previewer.

Hovering in the top right corner of my desktop activates it. All workplaces are shown, all active applications are shown, and if more than one application is running on a given workplace they are separated, so they can be clearly displayed. One click will switch your application and/or desktop.

I found that when I first started using it I was forever setting it off my mistake if, for example, I was a little too slow in closing off a maximized window. But like most of the problems I’ve found in Mint, it comes with its own solution. In this case, I simply increased the delay time to .4 seconds, and it works exactly as and when I want it to.

Conclusion

In many ways, Linux Mint is too deep to discuss in one article; in writing this, I had to discard quite a lot. Mint’s Screensaver comes to mind, but also Nemo File Manager’s many right-click options. But the plain truth is that there are widgets and applets, especially in “Extensions” I still have not gotten around to experimenting with.

Finally, I’ve been using a computer of some sort for at least 30 years. I had a Commodore, an Apple, and a DOS PC. I’ve used Microsoft ME through to Windows 10. In Linux, I’ve used Ubuntu pre- and post-Unity, Linux Mint Mate, Fedora, Arch and Zorin. Overall, these machines and systems and all this time, I’ve never had what I’m enjoying right now.