When you’re just starting out with Linux, it’s easy to get overwhelmed.

You probably know only Windows, but now you want to use Linux because you read that Linux is better than Windows as it’s more secure and you don’t have to buy a license to use Linux.

But then when you go about downloading and installing Linux, you learn that Linux is not a single entity. There’s Ubuntu, Fedora, Linux Mint, elementary and hundreds of other ‘Linux variants’. The trouble is that some of them look just like others.

Why are there so many Linux operating systems if that's the case? And then you also learn that Linux is just a kernel, not an operating system.

It gets messy. And you may feel like pulling your hair out. As someone with a receding hairline, I would like you to keep your own hair intact by explaining things in a way you can easily understand.

I’m going to use an analogy to explain why Linux is just a kernel, why there are hundreds of types of Linux and why, despite looking similar, they are different.

The explanation here may not be considered good enough for an answer in an exam or interview, but it should give you a better understanding of the topic.

Linux is just a kernel

Linux is not an operating system; it’s just a kernel.

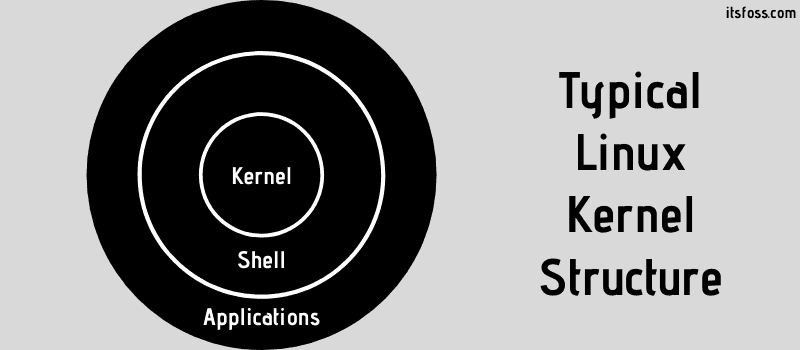

This statement is entirely true. But what does it mean? If you look at books, you’ll find the Linux kernel structure described like this:

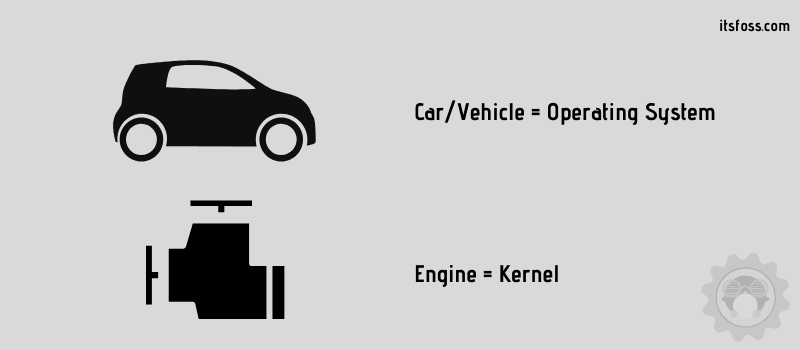

That is absolutely correct. However, let’s take a different approach. Think of operating systems as vehicles: any kind of vehicle, be it a motorbike, a car or a truck.

What is at the core of a vehicle? An engine.

Think of the kernel as the engine. It’s an essential part of the vehicle and you cannot use the vehicle without it.

But you cannot drive an engine, can you? You need many other things to interact with the engine and drive the vehicle. You need wheels, steering, gears, a clutch, brakes and more to drive a vehicle on top of that engine.

Similarly, you cannot use a kernel on its own. You need lots of tools to interact with the kernel and use the operating system. These things could be a shell, commands, the graphical interface (also called desktop environment), etc.

This makes sense, right? Now that you understand this analogy, let’s take it further so that you understand the rest of it.

Think of operating systems as vehicles

Think of Microsoft as an automobile company that makes a general-purpose car (the Windows operating system) that is hugely popular and dominates the car market. They use their own patented engine that no one else can use. But these ‘Microsoft cars’ do not offer any scope for customization. You cannot modify the engine on your own.

Now we come to the ‘Apple automobile’. They offer shiny-looking, luxury cars at an expensive price. If you have a problem, they have a premium support system where they might just replace the car.

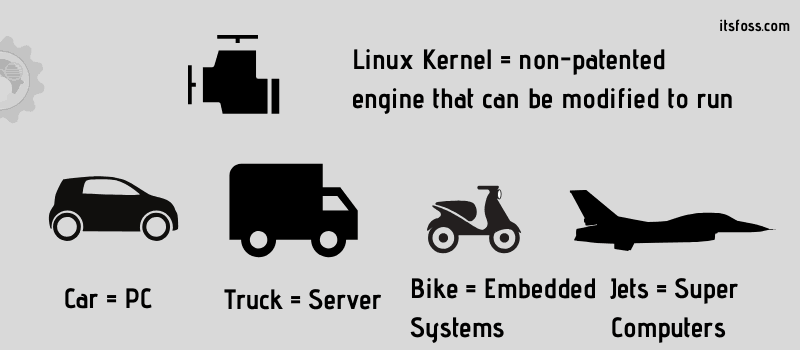

Now comes Linux. Remember, Linux is just an engine (kernel). But this ‘Linux engine’ is not patented and thus anyone is free to modify and build cars (desktop operating systems), bikes (small embedded systems in your toys, TVs, etc.), trucks (servers) or jet-planes (supercomputers) on top of it. In the real world, no such engine exists, but accept it for the sake of this analogy.

- kernel = engine

- Linux kernel = specific type of engine

- desktop operating systems = cars

- server operating systems = heavy trucks

- embedded systems = motorbikes

- desktop environments = body of the vehicle along with interiors (dashboard etc.)

- themes and icons = paint job, rim job and other customizable features

- applications = accessories you use for a specific purpose (like the music system)

Why are there so many Linux OS/distributions? Why do some look similar?

Why there are so many cars? Because there are several vehicle manufacturers using the ‘Linux engine’ and each of them has many cars of different types and for different purposes.

Since the ‘Linux engine’ is free to use and modify, anyone can use it to build a vehicle on top of it.

This is why Ubuntu, Debian, Fedora, SUSE, Manjaro and many other Linux-based operating systems (also called Linux distributions or Linux distros) exist.

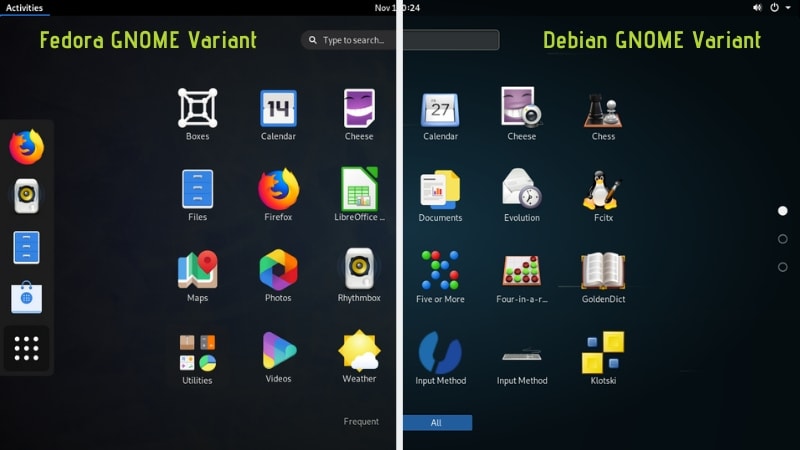

You might also have noticed that these Linux operating systems offer different variants, but they look similar. I mean, look at Fedora’s default GNOME version and Debian’s GNOME version. They do look the same, don’t they?

The component that provides the look and feel in a Linux OS is called the desktop environment. In our analogy, you can think of it as a combination of the outer body and matching interiors. This is what provides the look and feel for your vehicle, does it not?

Based on the exterior, you can classify the cars into categories: sedan, SUV, hatchback, station wagon, convertible, minivan, van, compact car, 4×4, etc.

But each ‘type of car’ is not exclusive to a single automobile company. Ford offers SUVs, compact cars, and vans. etc., and so do other companies like General Motors or Toyota.

Similarly, distributions (Linux OSes) like Fedora, Ubuntu, Debian, Manjaro, etc., also offer different variants in the form of GNOME, KDE, Cinnamon, MATE and other desktop environments.

Ford’s SUV may look similar to Toyota’s or Renault’s SUV. Fedora’s GNOME version may look similar to Manjaro or Debian’s GNOME version.

Some types of cars consume more fuel; some desktop environments need more RAM

You probably understand the ‘usefulness’ of different types of cars. Compact cars are good for driving in cities, vans are good for long trips with family, 4×4 are good for adventures in jungles and other rough terrains. An SUV may look good and feel comfortable to sit in, but it consumes more fuel than a compact car that might not be as comfortable.

Similarly, desktop environments (GNOME, MATE, KDE, Xfce, etc.) also serve a purpose other than just providing the looks for your Linux operating system.

GNOME provides a modern-looking desktop, but it consumes more RAM and thus requires that your computer has more than 4 GB of RAM. Xfce on the other hand, may look old/vintage, but it can run on systems with 1 GB of RAM.

Difference between getting desktop environments from the distribution and installing on your own

As you start using Linux, you’ll also come across opportunities to easily install other desktop environments on your current system.

Remember that Linux is a free world. You are free to modify the engine – customize the looks on your own – if you have the knowledge/experience or if you are an enthusiastic learner.

Think of it as like customizing cars. You may modify a Hundai i20 to look like a Suzuki Swift Dzire. But it might not be the same as using a Swift Dzire.

When you are inside the i20 modified to look like a Swift Dzire, you’ll find that it may not have the same experience from the inside. The dashboard is different, the seats are different. You may also notice that the exterior doesn’t fit the same on the i20’s body.

The same goes for switching desktop environments. You will find that you don’t have the same set of apps in Ubuntu that you would be getting in Mint Cinnamon. A few apps will look out of place. Not to mention that you may find a few things broken, such as a missing network manager indicator, etc.

Of course, you can put time, effort and skills into making the Hundai i20 look as much like a Swift Dzire as possible, but you may feel like getting a Suzuki Swift Dzire is a better idea in the first place.

This is the reason why installing Ubuntu MATE is better than installing Ubuntu (GNOME version) and then installing MATE desktop on it.

Linux operating systems also differ in the way they handle applications

Another major criterion by which the Linux operating systems differ from each other is package management.

Package management is basically how you get new software and updates for your system. It’s up to your Linux distribution/OS to provide security and maintenance updates. Your Linux OS also provides the means of installing new software on your system.

Some Linux operating systems provide all the new software versions immediately after their release, while some take time to test them for your own good. Some Linux systems (like Ubuntu) provide an easier way of installing new software, while you may find it complicated in others (like Gentoo).

Staying with our analogy, consider installing software like adding accessories to your vehicle.

Suppose you have to install a music system in your car. You may have two options here. Your car could be designed in such a way that you just insert the music player, you hear a click sound and you know it’s installed. Alternatively, you might have to get a screwdriver and then fix the music player in place with screws.

Most people would prefer the hassle-free click-lock installing system. Some people might take the matter (and the screwdriver) into their own hands.

If an automobile company provides scope for installing lots of accessories in click-lock fashion in their cars, they will be preferred, won’t they?

This is why Linux distributions like Ubuntu have more users because they have a huge collection of software that can be easily installed in a matter of clicks.

Conclusion

Before I conclude this article, I’ll also like to talk about support, which plays a significant role in choosing a Linux OS. For your car, you would like to have an official service center or other garages that service the automobile brand you own, wouldn’t you? If the automobile company is popular, naturally, it will have more and more garages providing services.

The same goes for Linux as well. For a popular Linux OS like Ubuntu, you have official forums for seeking support and a good number of other websites and forums providing troubleshooting tips to fix your problem.

Again, I know this is not a perfect analogy, but it helps understand things slightly better.

If you are completely new to Linux, did this article clarify things, or are you more confused than before?

If you already know Linux, how would you explain it to someone from a non-technical background?

Your suggestions and feedback are welcome.