If you have an Intel-chipset based motherboard, there are great chances it is equipped with the Intel Management (Intel ME) unit. This is not new. And concerns regarding the privacy issue behind that little know feature were raised for several years. But suddenly, the blogosphere seems to have rediscovered the problem. And we can read many half-true or just plain wrong statements about this topic.

So let me try to clarify, as much as I can, some key points for you to make your own opinion:

What is Intel ME?

First, let’s give a definition straight from Intel’s website:

Built into many Intel® Chipset–based platforms is a small, low-power computer subsystem called the Intel® Management Engine (Intel® ME). The Intel® ME performs various tasks while the system is in sleep, during the boot process, and when your system is running.

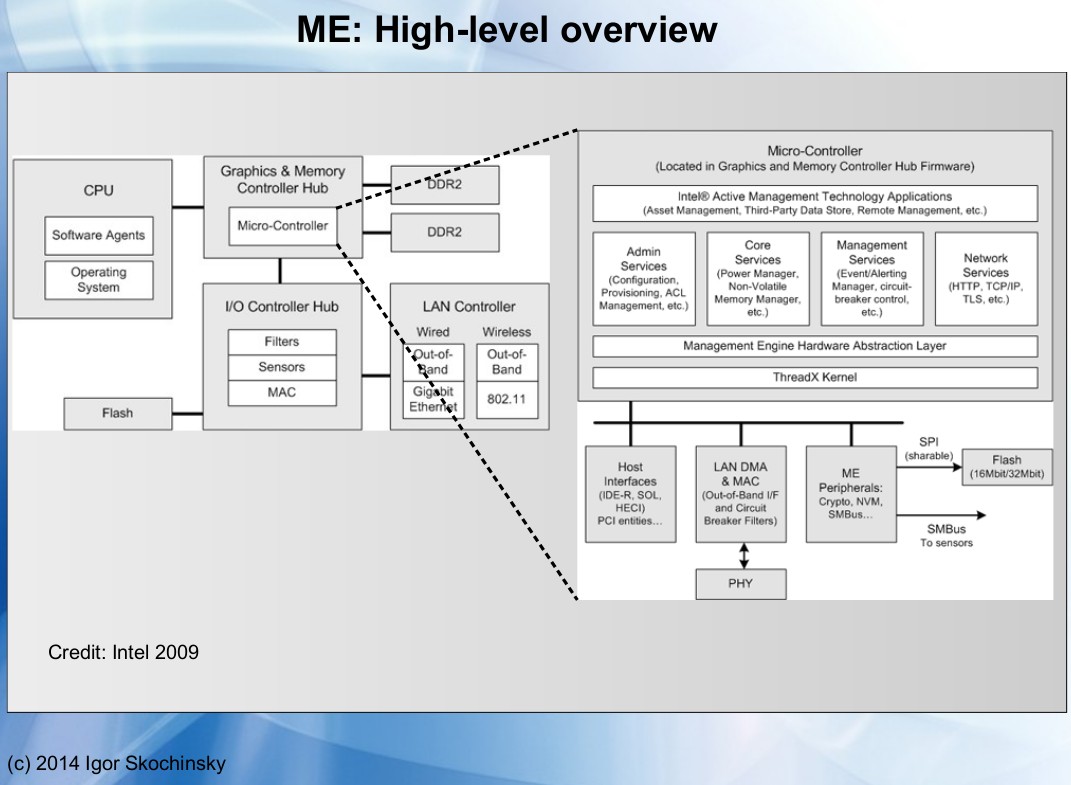

Simply said, that means Intel ME adds another processor on the motherboard to manage the other sub-systems. As a matter of fact, it is more than just a microprocessor: it’s a microcontroller with its own processor, memory, and I/O. Really just like if it was a small computer inside your computer.

That supplemental unit is part of the chipset and is NOT on the main CPU die. Being independent, that means Intel ME is not affected by the various sleep state of the main CPU and will remain active even when you put your computer in sleep mode or when you shut it down.

As far as I can tell Intel ME is present starting with the GM45 chipset—that brings us back to the year 2008 or so. In its initial implementation, Intel ME was on a separate chip that could be physically removed. Unfortunately, modern chipsets include Intel ME as part of the northbridge which is essential for your computer to work. Officially, there is no way to switch off Intel ME, even if some exploit seems to have successfully been used to disable it.

I read it runs on “ring -3” what does that mean?

Saying Intel ME as running in “ring -3” leads to some confusion. The protection rings are the various protection mechanisms implemented by a processor allowing, for example, the kernel to use certain processor instructions whereas applications running on top of it cannot do it. The key point is software running in a “ring” has total control over software running on a higher level ring. Something that can be used for monitoring, protection or to present an idealized or virtualized execution environment to software running in higher level rings.

Typically, on x86, applications run in ring 1, the kernel run in ring 0 and an eventual hypervisor on ring -1. “ring -2” is sometimes used for the processor microcode. And “ring -3” is used in several papers to talk about Intel ME as a way to explain it has even higher control than everything running on the main CPU. But “ring -3” is certainly not a working model of your processor. And let me repeat once again: Intel ME is not even on the CPU die.

I encourage you to take a look especially at the first pages of that Google/Two Sigma/Cisco/Splitted-Desktop Systems report for an overview of the several layers of execution of a typical Intel-based computer.

What is the problem with Intel ME?

By design, Intel ME has access to the other sub-systems of the motherboard. Including the RAM, network devices, and cryptographic engine. And that as long as the motherboard is powered. In addition, it can directly access the network interface using a dedicated link for out-of-band communication, thus even if you monitor traffic with a tool like Wireshark or tcpdump you might not necessarily see the data packet sent by Intel ME.

Intel claims that ME is needed to get the best of your Intel Chipset. Most useful, it can be used especially in a corporate environment for some remote administration and maintenance tasks. But, no one outside Intel knows exactly what it CAN do. Being close sourced that leads to legitimate questions about the capabilities of that system and the way it can be used or abused.

For example, Intel ME has the potential for reading any byte in RAM in search for some keyword or to send those data through the NIC. In addition, since Intel ME can communicate with the operating system—and potentially applications— running on the main CPU, we could imagine scenarios where Intel ME would be (ab)used by a malicious software to bypass OS level security policies.

Is this science fiction? Well, I’m not personally aware of data leakage or other exploit having used Intel ME as their primary attack vector. But quoting Igor Skochinsky can give you some ideal of what such system can be used for:

The Intel ME has a few specific functions, and although most of these could be seen as the best tool you could give the IT guy in charge of deploying thousands of workstations in a corporate environment, there are some tools that would be very interesting avenues for an exploit. These functions include Active Managment Technology, with the ability for remote administration, provisioning, and repair, as well as functioning as a KVM. The System Defense function is the lowest-level firewall available on an Intel machine. IDE Redirection and Serial-Over-LAN allows a computer to boot over a remote drive or fix an infected OS, and the Identity Protection has an embedded one-time password for two-factor authentication. There are also functions for an ‘anti-theft’ function that disables a PC if it fails to check in to a server at some predetermined interval or if a ‘poison pill’ was delivered through the network. This anti-theft function can kill a computer, or notify the disk encryption to erase a drive’s encryption keys.

I let you take a look at Igor Skochinsky presentation for the REcon 2014 conference to have a first-hand overview of the capabilities of Intel ME:

As a side note, to give you an idea of the risks take a look at the CVE-2017-5689 published in May 2017 concerning a possible privilege escalation for local and remote users using the HTTP server running on Intel ME when Intel AMT is enabled.

But don’t panic immediately because for most personal computers, this is not a concern because they do not use AMT. But that gives an idea of the possible attacks targeting Intel ME and the software running in there.

What do we know about Intel ME? How is it related to Minix?

Intel ME and the software running on top of it are close sourced, and people having access to the related information are bound by a non-disclosure agreement. But thanks to independent researchers we still have some information about it.

Intel ME shares the flash memory with your BIOS to store its firmware. But unfortunately, a large part of the code is not accessible by a simple dump of the flash because it relies on functions stored in the inaccessible ROM part of the ME microcontroller. In addition, it appears the parts of the code that are accessible are compressed using non-disclosed Huffman compression tables. This is not cryptography, its compression— obfuscation some might say. Anyway, it does not help in reverse engineering Intel ME.

Up to its version 10, Intel ME was based on ARC or SPARC processors. But Intel ME 11 is x86 based. In April, a team at Positive Technologies tried to analyze the tools that Intel provides to OEMs/vendor as well as some ROM bypass code. But due to Huffman compression, they weren’t able to go very far.

However, they were able to do was to analyze TXE, the Trusted Execution Engine, a system similar to Intel ME, but available on the Intel Atom platforms. The nice thing about TXE is the firmware is not Huffman encoded. And there they found a funny thing. I prefer quoting the corresponding paragraph in extenso here:

In addition, when we looked inside the decompressed vfs module, we encountered the strings “FS: bogus child for forking” and “FS: forking on top of in-use child,” which clearly originate from Minix3 code. It would seem that ME 11 is based on the MINIX 3 OS developed by Andrew Tanenbaum :)

Let make things clear: TXE contains code “borrowed” from Minix. That’s sure. Other hints suggest it probably runs a complete Minix implementations. Finally, despite no evidence, we can assume without too many risks that ME 11 would be based on Minix too.

Until recently Minix was certainly not a well known OS name. But a couple of catchy titles changed that recently. That and a recent open letter by Andrew Tannenbaum, the author of Minix, are probably at the root of the current hype around Intel ME.

Andrew Tanenbaum?

If you don’t know him, Andrew S. Tanenbaum is a computer scientist and professor emeritus at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam in the Netherlands. Generations of students, including me, have learned computer sciences through Andrew Tanenbaum books, work, and publications.

For educational purposes, he started development of the Unix-inspired Minix operating system in the late 80s. And was famous for its controversy on Usenet with a then young guy named Linus Torvalds about the virtues of monolithic versus micro-kernels.

For what interests us today, Andrew Tanenbaum has declared not having any feedback from Intel about the usage they have made of Minix. But in an open letter to Intel, he explains he was contacted a few years ago by Intel engineers asking many technical questions about Minix and even requesting code change to being able to selectively remove part of the system in order to reduce its footprint.

According to Tannenbaum, Intel never explained the reason for their interest in Minix. “After that initial burst of activity, there was radio silence for a couple of years”, that is up until today.

In a final note, Tannenbaum explains its position:

For the record, I would like to state that when Intel contacted me, they didn’t say what they were working on. Companies rarely talk about future products without NDAs. I figured it was a new Ethernet chip or graphics chip or something like that. If I had suspected they might be building a spy engine, I certainly wouldn’t have cooperated […]

Worth mentioning if we can question the moral behavior of Intel, both regarding the way they approached Tannenbaum and Minix and in the aim pursued with Intel ME, strictly speaking, they acted perfectly in accordance with the terms of the Berkeley license accompanying the Minix project.

More information on ME?

If you’re looking for more technical information about Intel ME and the current state of the community knowledge of that technology, I encourage you to take a look at the Positive Technology presentation published for the TROOPERS17 IT-Security conference. While not easily understandable by everyone, this is certainly a reference to judge the validity of information read elsewhere.

And what about using AMD?

I’m not familiar with AMD technologies. So if you have more insight, let us know using the comment section. But from what I can tell, the AMD Accelerated Processing Unit (APU) line of microprocessors have a similar feature where they embed an extra ARM-based microcontroller, but this time directly on the CPU die. Amazingly enough, that technology is advertised as “TrustZone” by AMD. But like for its Intel counterpart, no one really know what it does. And no one has access to the source to analyze the exploit surface it adds to your computer.

So what to think?

It is very easy to become paranoid about those subjects. For example, what proves the firmware running on your Ethernet or Wireless NIC don’t spy at you to transmit data through some hidden channel?

What makes Intel ME more a concern is because it works at a different scale, being literally a small independent computer looking at everything happening on the host computer. Personally, I fell concerned by Intel ME since it’s initial announcement. But that didn’t prevent me from running Intel-based computers. Certainly, I would prefer if Intel made the choice to open-source the Monitoring Engine and the associated software. Or if they provided a way to physically disable it. But that’s an opinion that only regards me. You certainly have your own ideas about that.

Finally, I said above, my goal in writing that article was to give you as much as possible verifiable information so you can make your own opinion…