You’ll hear the acronym, or read about it: POSIX, on different online boards and articles. Programmers and system developers seem to worry about it the most. It can sound mysterious and, while there are many good sources on the subject, some discussion boards (brevity is part of their nature), don’t go into detail as to what it is and this can lead to confusion. What, then, is POSIX, really?

What is POSIX?

POSIX isn’t actually a thing. It describes a thing – much like a label. Imagine a box labeled: POSIX, and inside the box is a standard. A standard consists of sets of rules and instructions that POSIX is concerned with. POSIX is shorthand for Portable Operating System Interface. It is an IEEE 1003.1 standard that defines the language interface between application programs (along with command line shells and utility interfaces) and the UNIX operating system.

Compliance to the standard ensures compatibility when UNIX programs are moved from one UNIX platform to another. POSIX’s focus is primarily on features from AT&T’s System V UNIX and BSD UNIX.

A standard must be spelled out and followed by rules on how to achieve the goal of interoperability between operating systems. POSIX covers such things as: System Interfaces, and Commands and Utilities, Network File Access, just to name a few – there is much more to POSIX than this.

Why POSIX?

In a word: portability.

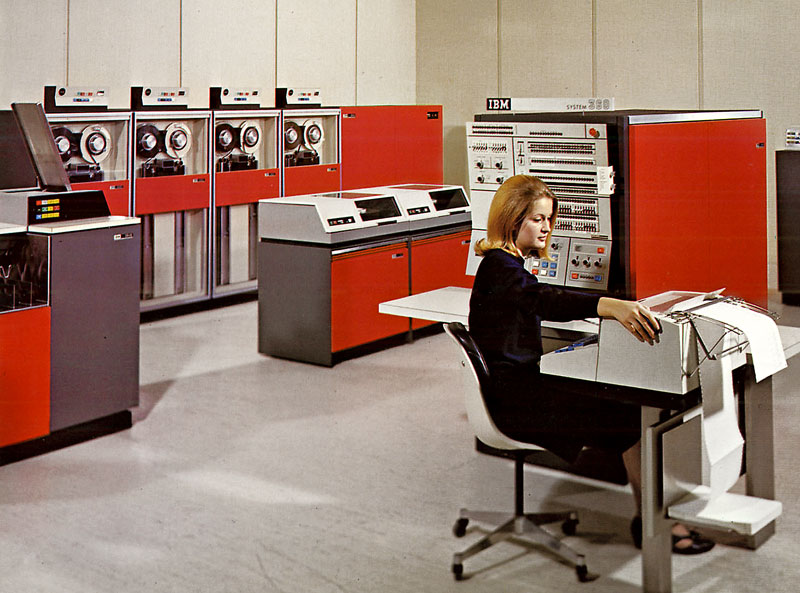

Over 60 years ago, programmers had to rewrite code completely if they wanted their software to run on more than one system. This didn’t happen all that often due to the expense involved, but portability became a feature in the mid-1960s – not through POSIX – but in the mainframe arena.

IBM introduced the System/360 family of mainframe computers. Different models had their unique specializations, but the hardware was such that they could use the same operating system: OS/360.

Not only could the operating system run on different models, applications could run on them as well. Not only did this keep costs low, but it created computer systems – systems across a product line that could work together. It’s all common today – networks and systems, but back then, this was a huge deal!

When UNIX came about, around the same time, it also showed promise in that it could operate on machines from different manufacturers. However, when UNIX started to fork into different flavors, porting code across these UNIX variants became difficult. The promise of UNIX portability was losing ground.

To solve this portability issue POSIX was formed in the 1980s. The standard was defined based on AT&T’s System V UNIX and BSD UNIX, the two biggest variants at the time. It’s important to note that POSIX wasn’t formed to control how the operating systems were built – any company was free to design their UNIX variant any way they pleased. POSIX was only concerned with how an application interfaces with the operating system. In programmer-speak, an interface is the method one program’s code can communicate with another program. The interface expects Program A to provide a specific type of information to Program B. Likewise, Program A expects Program B to answer back with a specific type of data.

For example, if I want to read a file using the cat command, I would type something like this on the command line:

cat myfile.txtWithout going into a lot of programmer-speak, I’ll just say that the cat command makes a call to the operating system to fetch the file so cat can read it. cat reads it and then displays the file’s contents on the screen. There is a lot of interplay between the application (cat) and the operating system. How this interplay works is what POSIX was interested in. If the interplay could be the same across the different UNIX variants, portability – regardless of operating system, manufacturer, and hardware – is regained.

The specifics as to how all of this is accomplished is defined in the standard.

Compliance is Voluntary

All of us have at least seen a message like, “for help, type: xxxxx –help.” This is common in Linux and is not POSIX compliant. POSIX never required the double-dash, they expect one dash. The double-dash comes from GNU, yet, it doesn’t harm Linux and adds a little to its character. At the same time, Linux is mostly compliant, especially when it comes to system call interfaces. This is why we are able to run X, GNOME, and KDE applications on Linux, Sys V UNIX, and BSD UNIX. Various commands, such as ls, cat, grep, find, awk, and many more operate the same across the different variants.

As a rule, compliance is a willing step. When code is compliant, it’s easier to move to another system; very little code rewrite, if any, would be necessary. When code can work on different systems, the use of it expands. People using other systems can benefit from the use of the program. For the budding programmer, learning how to write programs that are POSIX compliant can only help their career. For those readers who are interested in the Linux sphere of compliance, much good information can be found at: Linux Standard Base.

But I’m Not a Programmer or System Designer…

Many people who work on computers aren’t programmers or operating system designers. They’re the medical transcription clerks, secretaries who write out letters, task lists, dictated memos, and so on. Others tabulate numbers, gather and massage data, run online stores, write books and articles (and some of us read them). In almost every job, there’s probably a computer close by.

POSIX affects these users too, whether they know it or not. Users don’t have to comply with the standard, but they do expect their computers to work. When operating systems and programs conform to the POSIX standard, they gain the benefit of interoperability. They will be able to move from one system to another with the reasonable expectation that the machines will work much like another one does. Their data will still be accessible and they will still be able to make changes to it.

POSIX, as well as other standards, are continually evolving. As technology grows, so does the standard. Standards are actually an agreed-upon system used by people, manufacturers, organizations, etc. to perform tasks in an efficient manner. Devices from one manufacturer is able to work with another manufacturer’s device. Think about it: Your Bluetooth earpiece can be used on an Apple iPhone just as well as it can on an Android phone. Our TV can hook up to, and stream, videos and shows from different networks, such as Amazon Prime, BritBox, Hulu – just to name a few. Now, we can even monitor out heart rate with our phones. All of this is made possible, largely in part, from compliance to standards.

Benefits galore. I like that.

So what about the X?

I admit it, I never said what the “X” was for in POSIX. Opensource.com has an excellent article where Richard Stallman explains what the “X” in POSIX means. Here it is, in his words:

The IEEE had finished developing the spec but had no concise name for it. The title said something like “portable operating system interface,” though I don’t remember the exact words. The committee put on “IEEEIX” as the concise name. I did not think that was a good choice. It is ugly to pronounce—it would sound like a scream of terror, “Ayeee!”—so I expected people would instead call the spec “Unix.”

Since GNU’s Not Unix, and it was intended to replace Unix, I did not want people to call GNU a “Unix system.” I, therefore, proposed a concise name that people might actually use. Having no particular inspiration, I generated a name the unclever way: I took the initials of “portable operating system” and added “ix.” The IEEE adopted this eagerly.

Conclusion

The POSIX standard allows developers to create applications, tools, and platforms on many operating systems using much of the same code. It isn’t a requirement, by any means, to write code according to the standard, but it does help, in a big way, when you want to port your code to other systems.

Basically, POSIX is geared toward operating system designers and software developers, but as users of a system, we are affected by POSIX whether we may realize it or not. It is because of the standard that we are able to work on one UNIX or Linux system and bring that work over to another system and work on it with no hiccups. As users, we gain numerous benefits in usability and data re-use across systems.