Many people who have never used Linux assume you must use the terminal to get anything done on the desktop. That belief used to be fair. For a long time, even basic tasks, like sound tweaks, Bluetooth fixes, or simple system changes, often meant copying commands from a forum post or editing config files you barely understood.

That history still shapes Linux’s reputation, even though the desktop has moved on. Modern Linux desktops now include polished graphical tools for a huge range of everyday workflows. The terminal is still there, and still powerful, but it is no longer the entry fee. Here are 16 things that we used to do in terminal 20 years ago. We can still do these in terminal, but that's a choice, not a compulsion.

1. System Updates and Upgrades

We'll start with this one because it's probably the most common misconception about Linux due to the fact that, for convenience, we still get terminal commands for handling updates and upgrades in most guides and tutorials. But while pasting commands in the terminal is convenient, it's no longer necessary, not by a long shot.

Whether you're updating distro-native packages or using Flatpak, Snap or even AppImage, you can usually use a graphical solution. Terminal commands just happen to be the most universally accepted method across the community. It's a bit of a relic from the way things used to be.

Useful tools for handling system updates:

- Update Manager: Ubuntu-based distros come with an update manager

- GNOME Software: GNOME's official "app store", supports managing updates for all kinds of packages (distro-native, Flatpak, and Snap), depending on the plugins installed

- Discover (KDE): The official "app store" for the KDE Plasma desktop environment, Discover also lets you manage updates across all sorts of packaging systems (distro-native, Flatpak, and Snap)

- Bazaar (Flatpak only): Bazaar is a Flatpak-specific "app-store" style tool that make Flatpak management easier, including updates

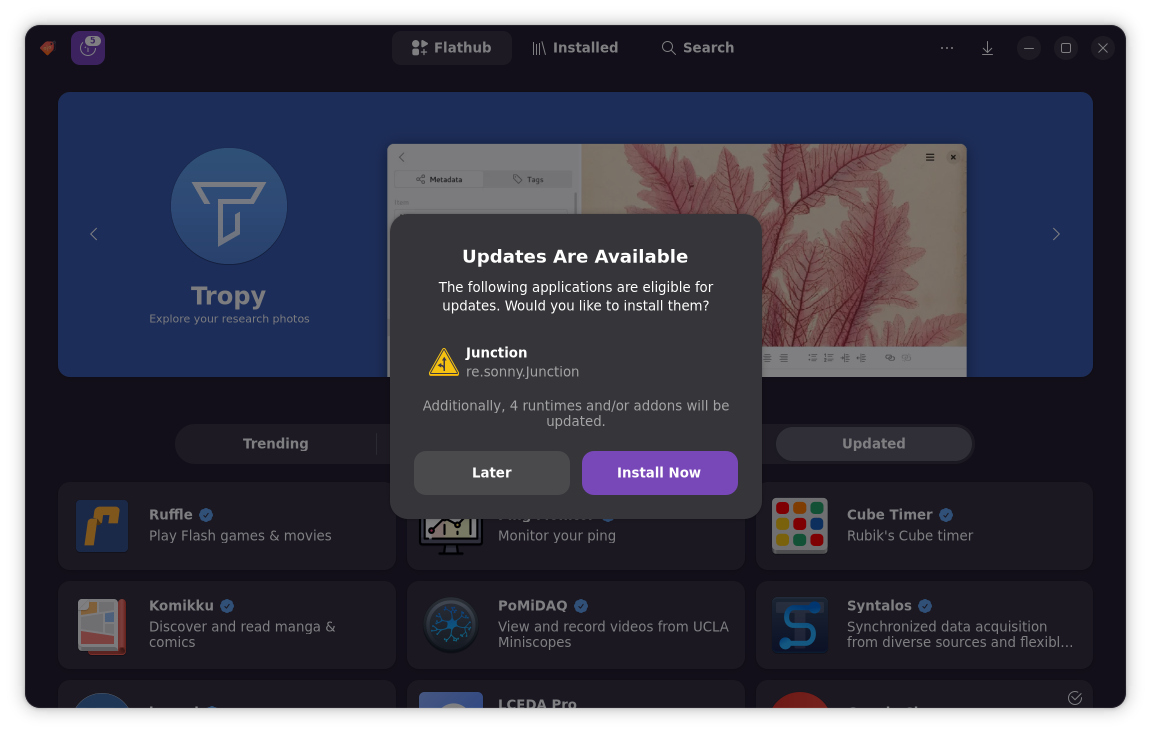

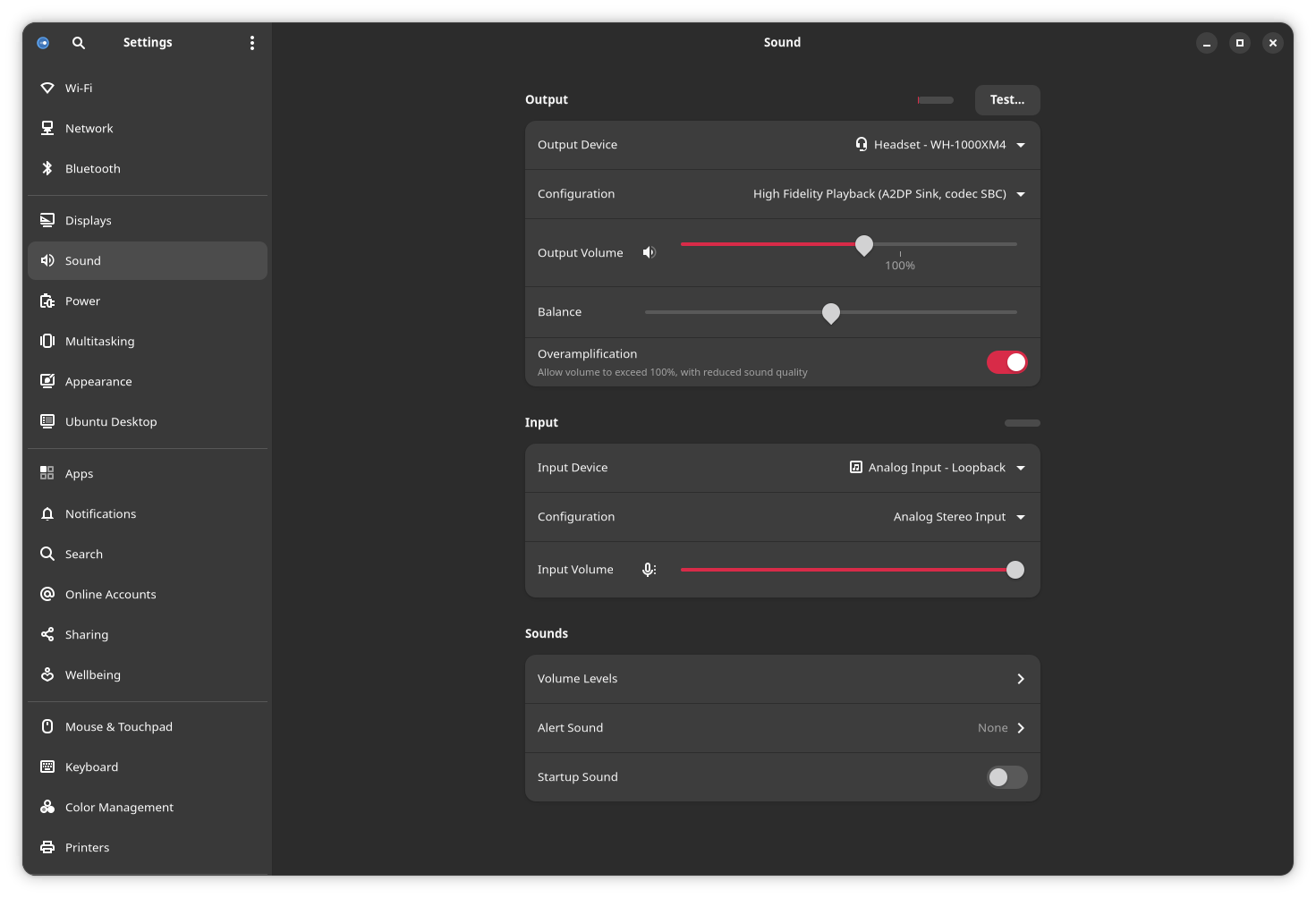

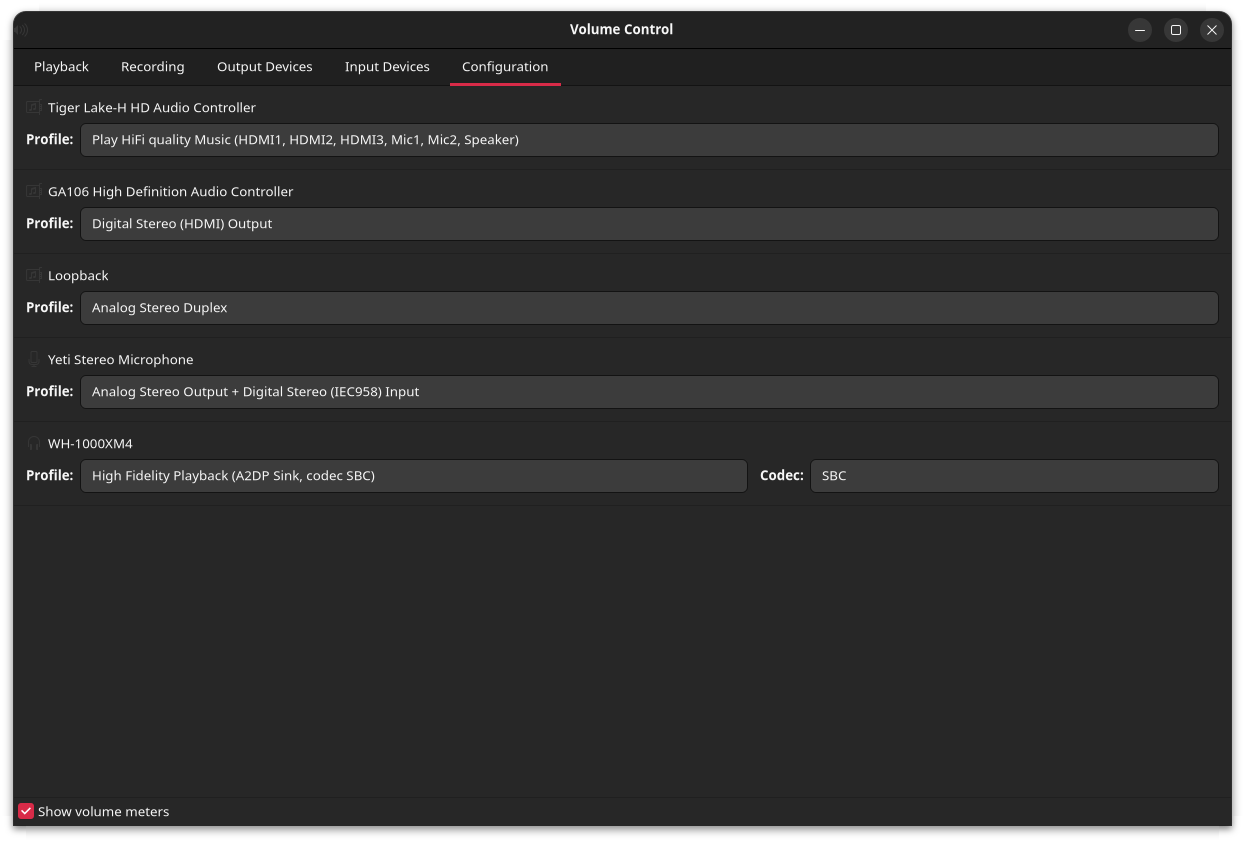

2. Audio Setup, Routing & Troubleshooting

Back in the early days of Linux, getting sound to work wasn’t just a hassle, it was a nightmare. I’ll never forget the seemingly sentient quirks I’d encounter with some chipsets, especially on (ironically) some of the most common computer brands at the time. You’d fix a problem with alsamixer only for it to creep back in the very moment you disconnected your headphones or sometimes just looked at the computer funny. And the only fixes available involved running scripts you found on forums and hoping for the best.

Thankfully, those days are over. In most cases, your standard desktop volume settings panel should cover most of what people used to fix by tinkering with commands and configs. Better yet, when you do need more control such as routing audio between apps, or fixing weird device quirks, you can rely on various graphical tools to make it far less painful than it used to be. Typically, a couple clicks is all you need to fix most issues these days.

Useful GUI tools for audio:

- Most desktop environments: Your desktop’s built-in sound settings

- PulseAudio Volume Control (pavucontrol): great for quick routing and configuration fixes (also works with Pipewire)

- Helvum: PipeWire patchbay-style routing

- qpwgraph: PipeWire graph manager, more advanced

3. Firewall Configuration

This is one that many people from the old school of the Linux desktop probably didn't even think much about until relatively recently. There was the presumption that Linux distros came without open ports anyway, so running a firewall was pretty much unnecessary. Plus, most popular distros at the time already shipped with a firewall installed (like Ubuntu and its derivatives with UFW).

The unspoken contract with this, though, was that when it came time to set up a firewall, you'd have to jump into the terminal and fiddle around with commands that could be intimidating if you didn't know your stuff. At least, that was then. These days, we have tools that let you configure a firewall with a normal interface. No need to mess with iptables any more (unless you want to, of course).

Firewall tools you can use graphically:

- Gufw: A simple UFW front-end (available on Ubuntu and its derivatives)

- KDE Plasma Firewall Settings: A Plasma-friendly firewall settings module

- Firewalld GUI: common on Fedora/RHEL and derivatives/related distros

- OpenSnitch: a frontend for the Snitch firewall service

4. Using Virtual Machines (With QEMU)

Running virtual machines through hardware virtualization tools like QEMU/KVM once used to feel like terminal-only territory. If you weren't willing to use VirtualBox or pay for VMware, and you wanted to run a VM, you were often knee-deep in commands, config files, and high-level advice that assumed you already knew what you were doing.

In those earlier times, VirtualBox and VMware existed, but on Linux they were often more finicky than people remember. Kernel updates often broke their out-of-tree modules, features lagged, and getting everything ‘just right’ wasn’t always worth the effort on the hardware many of us had.

Thankfully, times have changed, a lot. On most distros today, you can install a VM app and handle the entire workflow graphically: creating machines, attaching ISOs, allocating resources, managing storage, and even adjusting networking, all without typing a thing (except a VM name, of course).

Good GUI tools for the job:

- GNOME Boxes: simple, friendly, solid defaults, minimal configuration

- virt-manager: full-featured front-end for QEMU/KVM

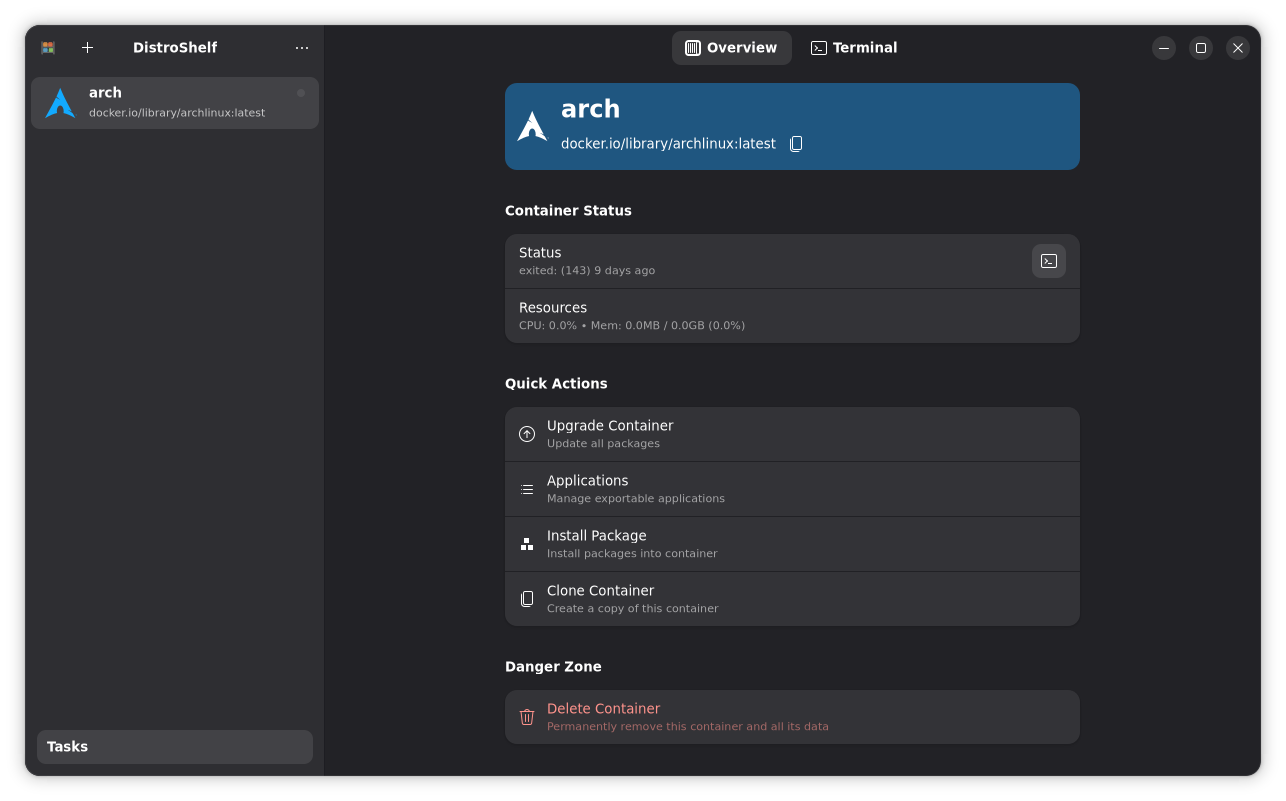

5. Running Containers

Containers are still the domain of the command-line, and with good reason, as they're still mainly the domain of servers and homelabs. Popular solutions like Docker and Podman are rightfully built for the terminal, to minimize overhead and to make management easier for server admins. Yet, this doesn't mean that you can't manage containers without dipping your toes into the CLI. In fact, you can perform most container-related tasks from the GUI with the right tools.

Many applications are now distributed within containerized distribution formats, and you might not even realize it. For instance, Snap and Flatpak are technically containerized solutions. But if we're being more strict about it, tools like DistroShelf and Docker Desktop have all but eliminated the need for the command line in setting up and managing containers, whether for applications or even entire distros.

You can pull images, start/stop containers, check logs, monitor resource use, manage volumes, and update your applications — all from the GUI.

GUI tools that make container management friendlier:

- Podman Desktop: a modern, desktop-focused container manager

- BoxBuddy: a handy GUI for managing Distrobox

- Vanilla OS and BlendOS: Distros that bake GUI container distro management right into the default experience

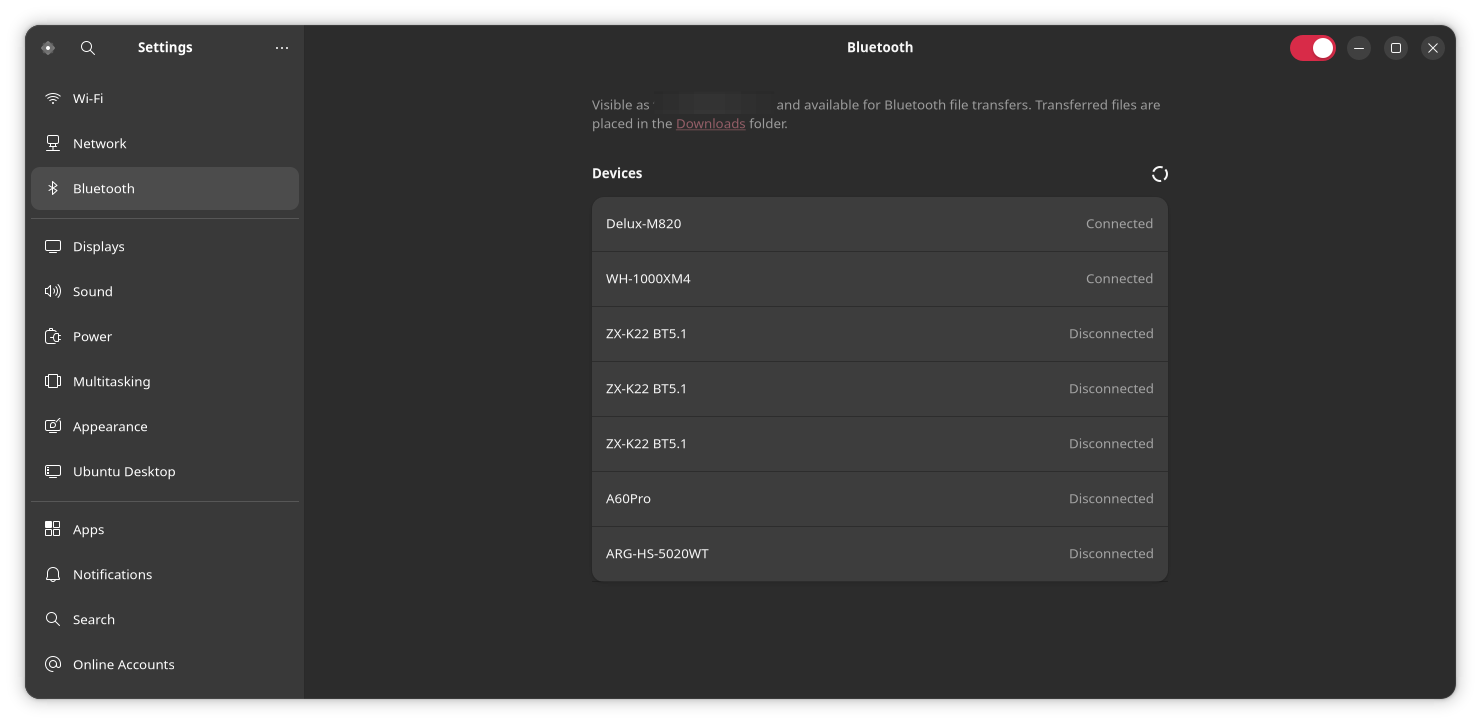

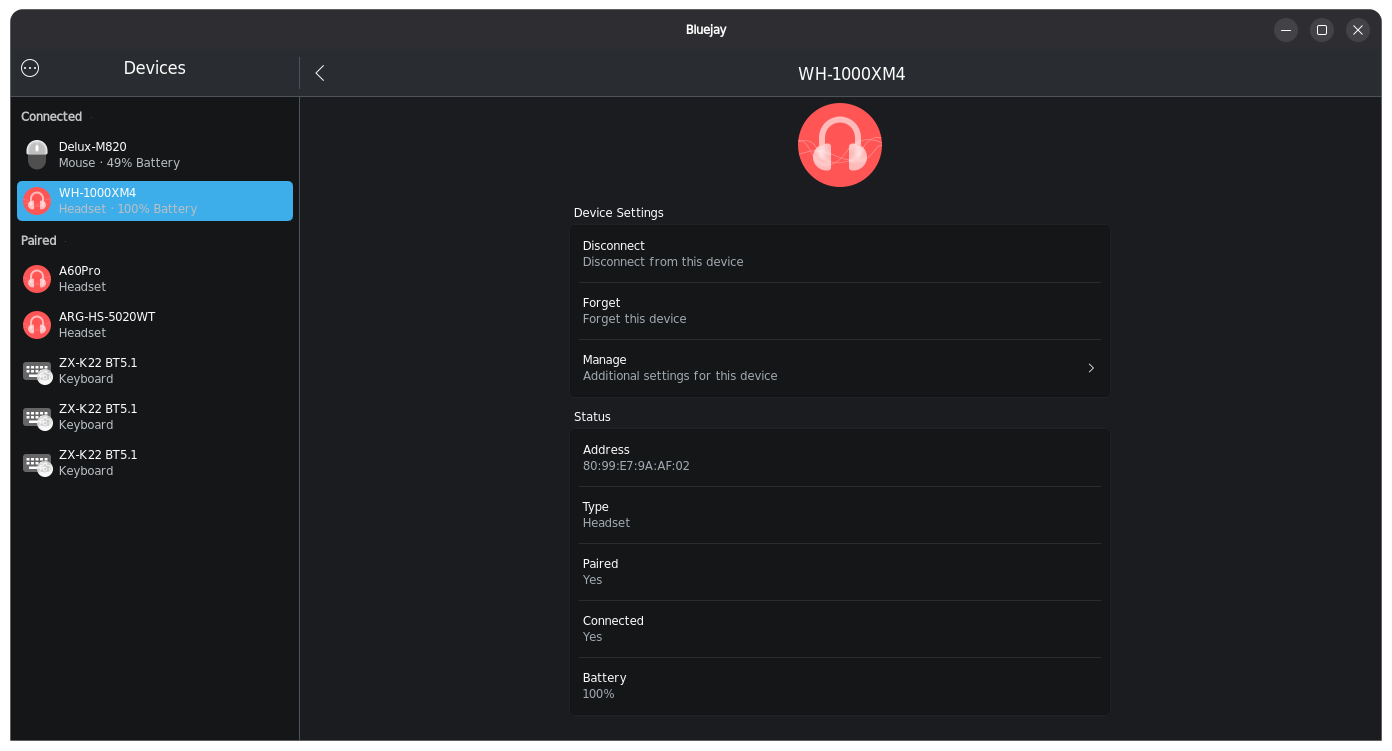

6. Bluetooth Devices and Pairing

Bluetooth is another area where Linux unfortunately earned a reputation for needing the terminal to be usable, even though we've had GUI solutions for quite some time. There was still the problem of shoddy chipset support, pairing failures, audio devices refusing to reconnect, and adapters misbehaving. Even with the development of a more robust Bluetooth stack, you'd still often find yourself hunting down commands in forums and hoping for the best.

These days, for the most part, those days are behind us. You just open your desktop environment's settings, find the Bluetooth panel, pair, connect, remove, or switch devices, no real hassle. Many of the common issues of the past are resolved, and Bluetooth management is a seamless workflow, especially on popular desktops like GNOME, KDE, and XFCE.

Better yet, some of the older tools have continued to grow with the times, so if you need a little more control (trust settings, advanced adapter behaviour, etc), there are also dedicated GUI managers for those tasks.

Bluetooth tools you can actually use without drama:

- GNOME/KDE/XFCE (and others): Most desktop environments have Bluetooth control modules in their system settings

- Bluejay: A Kirigami-based bluetooth device manager

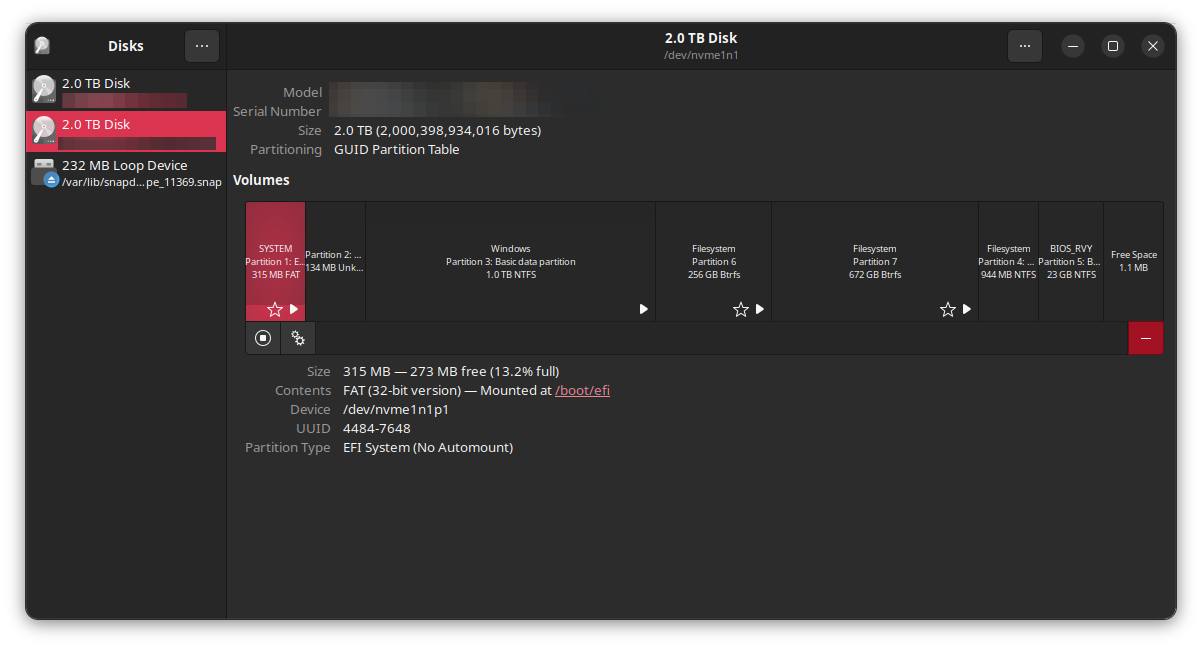

7. Disc Management

Managing disks (hard drives and, later, SSDs) on Linux used to be quite the pain at one time. For many tasks, if you couldn't boot into a Live CD, and sometimes even if you could, you'd need to fire up the terminal and run tools like fdisk to handle what often felt like scary work. The only “safe” option, if you didn't feel comfortable in the terminal, was not to mess around at all. Messing up a command could leave you with lost files, or worse, a broken file system.

Fast-forward to today, and most everyday disk work can be done with solid graphical tools, without having to fire up a live session on another drive. Need to format a USB drive, create partitions, check SMART data, or inspect a disk?

You can do it with a few clicks, often with tools built right into the system (on some distros).

Solid disk and partition tools:

- GNOME Disks: formatting, partitions, SMART checks, disk images

- GParted: Less commonly used these days, but still a worthy mention, a powerful partition editor (and still being maintained!)

- KDE Partition Manager: Plasma-friendly partitioning

- Disk Usage Analyser (Baobab): find what’s eating your space

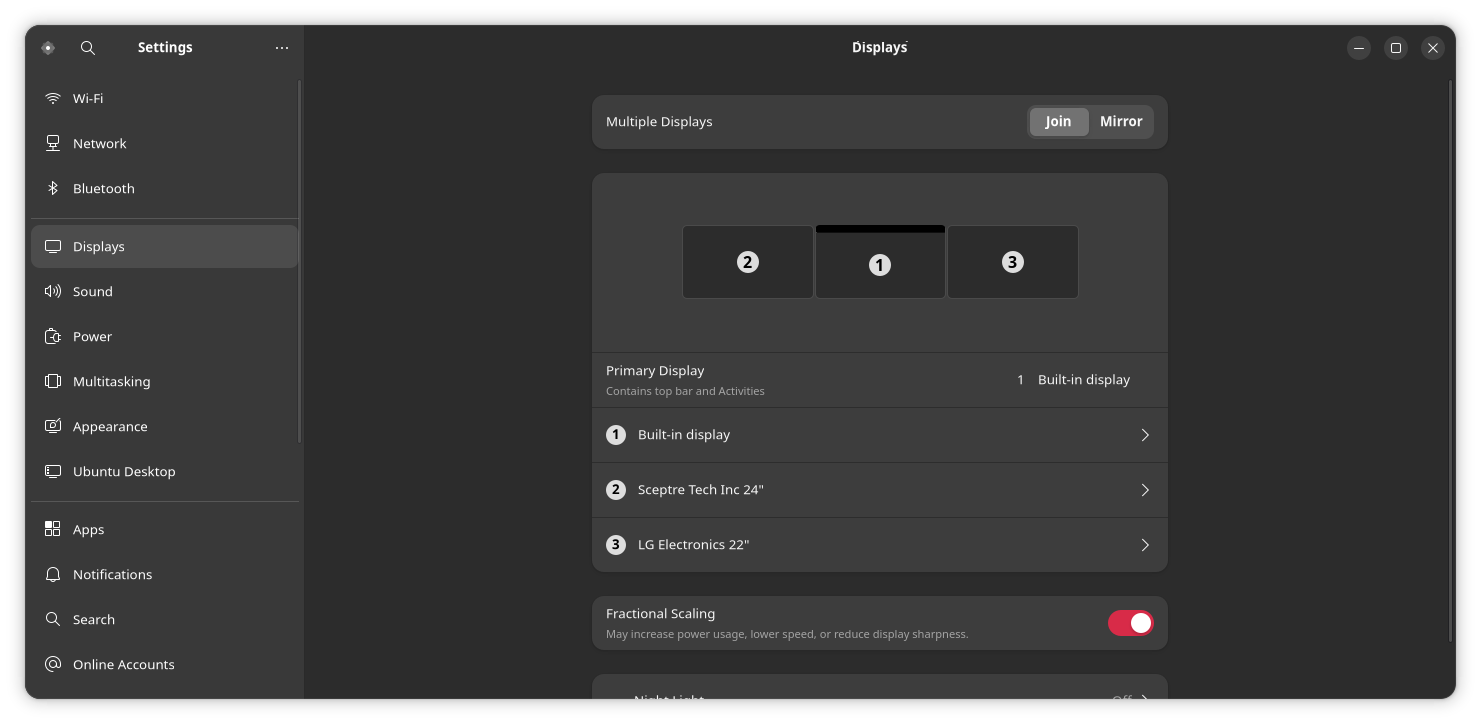

8. Multi-monitor Layouts, Scaling & Refresh Rates

Trust me, if you don't know the pain this one used to bring, consider yourself blessed. Display support on Linux at one time was quite the hassle. Adding a second display could turn into a mess: monitors not being detected, incorrect resolutions or positions, and broken refresh rates. Add to that, at one point UI scaling (at the desktop level) wasn't even a thing, though monitors already supported it.

Some people may remember when we relied on xrandr, not because we wanted to, but because we had to. Furthermore, if you go back far enough, you might remember the mystic arts of editing /etc/x11/xorg.conf by hand just to get a display layout to stick (or in some cases, to have a working display... at all). Needless to say, I don't miss those days.

Now, display management and multi-monitor setup is typically a "no-brainer"; you just hop into system settings, set your layout, and you're done, no terminal commands or trips to a TTY to think about. With Wayland bring even more robust per-monitor scaling and refresh rate support, most things should "just work" on modern desktops, even rare if edge cases still exist.

GUI tools that handle this well:

- GNOME Settings: Displays panel

- KDE System Settings: Display and Monitor panel

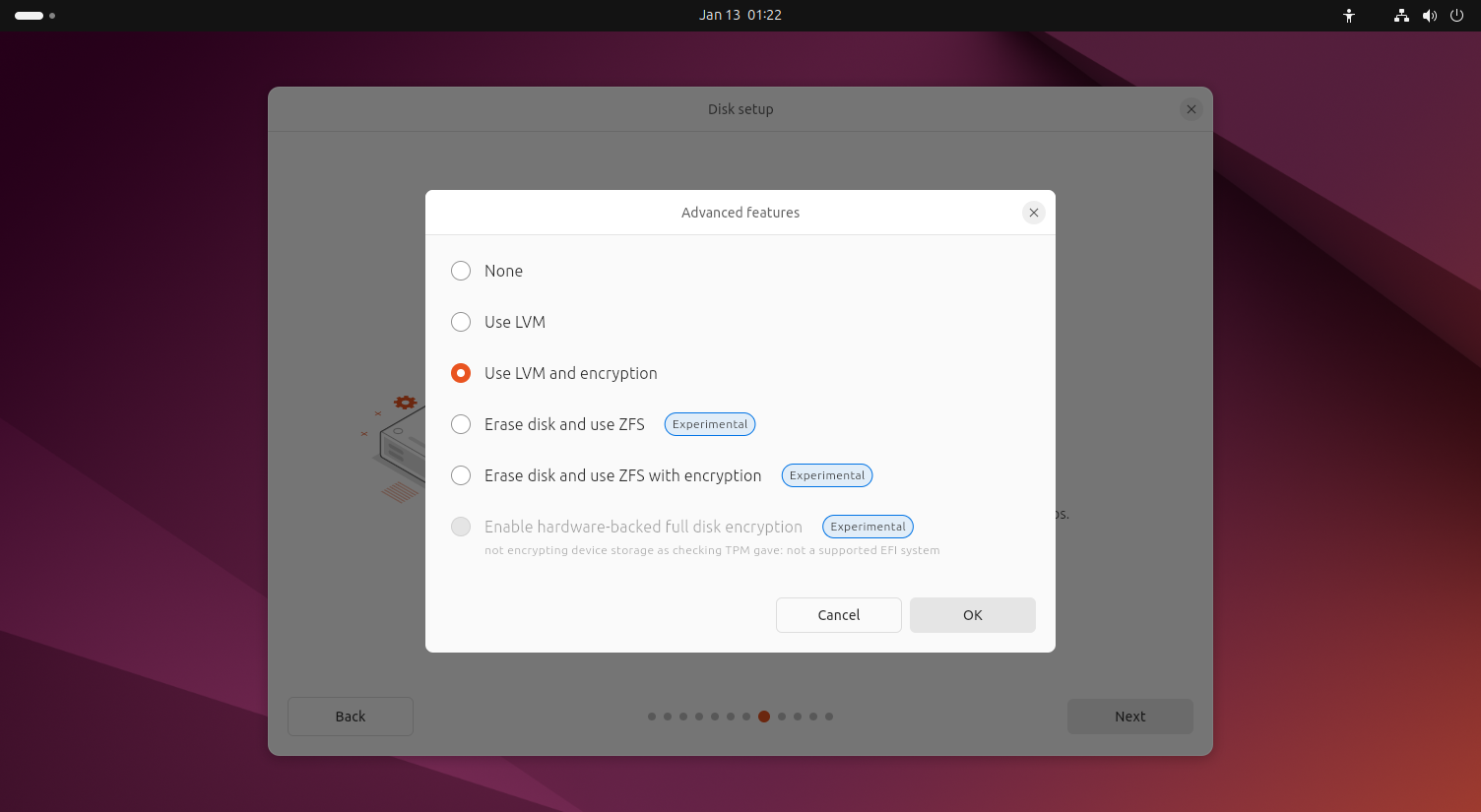

9. Disk Encryption (LUKS) Without the Terminal

Setting up disk encryption used to be one of those "power users only” tasks that almost always required dropping into the command line. It certainly wasn't exposed as an install option on most distros and if you wanted to encrypt a drive (or even just a USB stick), you'd need to be comfortable doing everything in the terminal and making sure you got every command just right. Beyond just being terminal-only affair, it wasn't a trusted Linux workflow to begin with, because it was so easy for something to go wrong.

These days, full-disk encryption is often offered right in the installer, and even after installation, you can still encrypt additional/external drives and partitions from the desktop with normal graphical tools. You can create/unlock encrypted volumes, change passphrases, and manage auto-unlock behaviour (where supported) without ever needing to touch the terminal.

The CLI workflow is still there for advanced setups and recovery work, of course, because ultimately, most GUI solutions are just sitting on top of the CLI apps that already existed.

GUI tools that make disk encryption more approachable:

- GNOME Disks: Lets you create and manage LUKS-encrypted partitions, unlock/lock volumes, and change passphrases

- KDE Partition Manager: Great for partitioning workflows that pair well with encrypted setups

- Many distro installers: Full-disk encryption is just a checkbox away

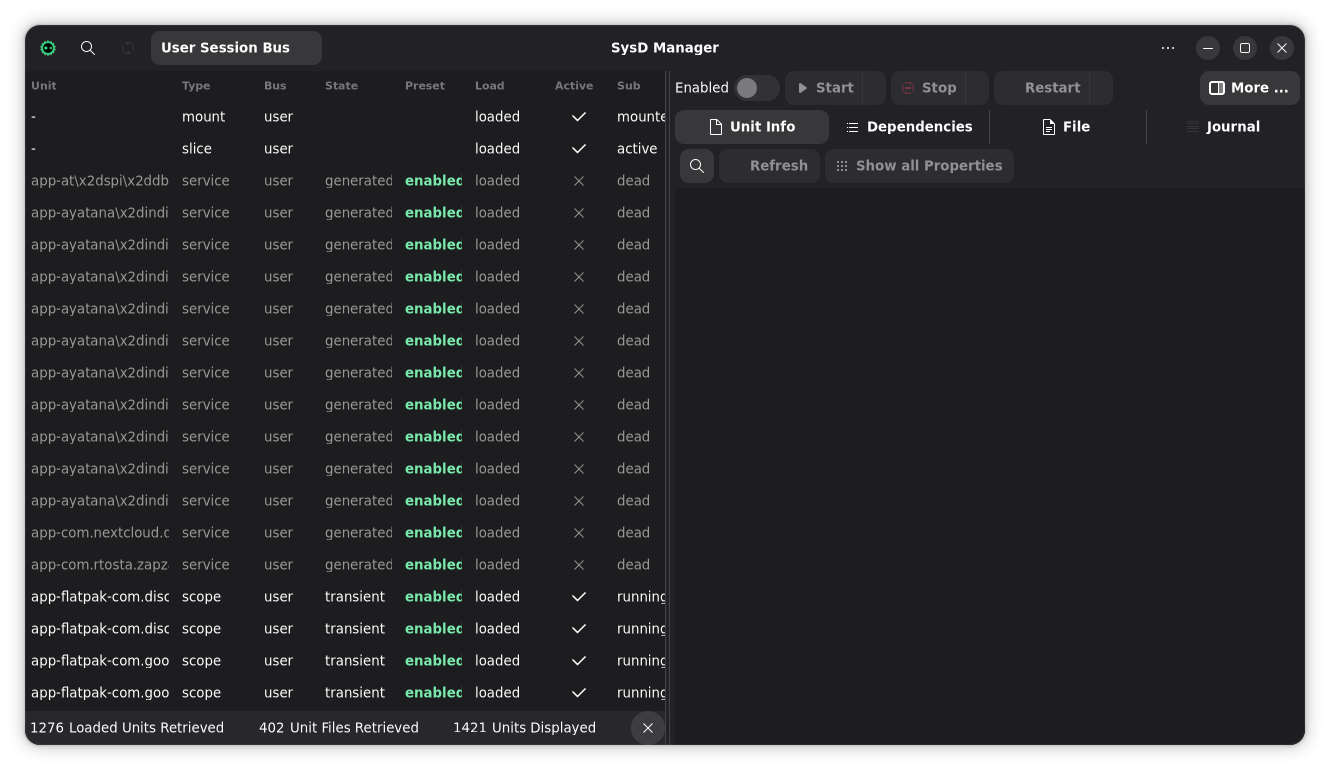

10. Managing System Services

At one time, if you wanted to manage what services start with your system, or manage services that are already running, you really had no choice but to use the terminal. It used to be that you had to either know the commands for your init system, or edit configuration files by hand. Granted, most tutorials these days (built for systemd) will still tell you to run systemctl to manage system services, but there are real, solid options readily available for most distros now.

To be fair, this is still an area where most distributions don't come with a built-in GUI solution, in part because the average user won't ever need (or want) to granularly manage system services. Thankfully, for those of us who do, there are several solutions available so we can easily handle this without ever typing a single command.

GUI solutions for managing services:

- SystemD Manager: A dedicated GUI for managing systemd services and see their status and output

- jdSystemMonitor: A versatile system monitoring tool that also lets you manage your systemd services (for an in depth look, see my review)

- CTL Dash: A dedicated system service tool for the COSMIC Desktop (works on other desktops as well)

11. USB Imaging & Recovery Media

This is one of the biggest improvements on the Linux desktop. We've been using live CDs and USBs for many years now, but while we've had graphical solutions for quite some time, the quirks and limitations we'd encounter would often force us back to the reliability of the command line. Furthermore, some distros didn’t ship a graphical imaging tool by default (or the one they provided wasn’t reliable for all kinds of ISOs), so you’d end up relying on dd or distro-specific scripts..

Now, we've got multiple polished GUI tools that make USB imaging simple, safe, and beginner-friendly, even to the point that some tools do the download and verification steps for you.

Reliable tools for writing ISOs:

- balenaEtcher: A popular tool for writing bootable disk images for any OS to USB drives

- KDE ISO Image Writer: A simple tool for creating bootable drives

- GNOME Disks: Not only can you use Disks for formatting drives, you can also wipe partitions and flash disk images to your drives

- Impression: A slick and straightforward tool for creating bootable drives. Part of the GNOME Circle

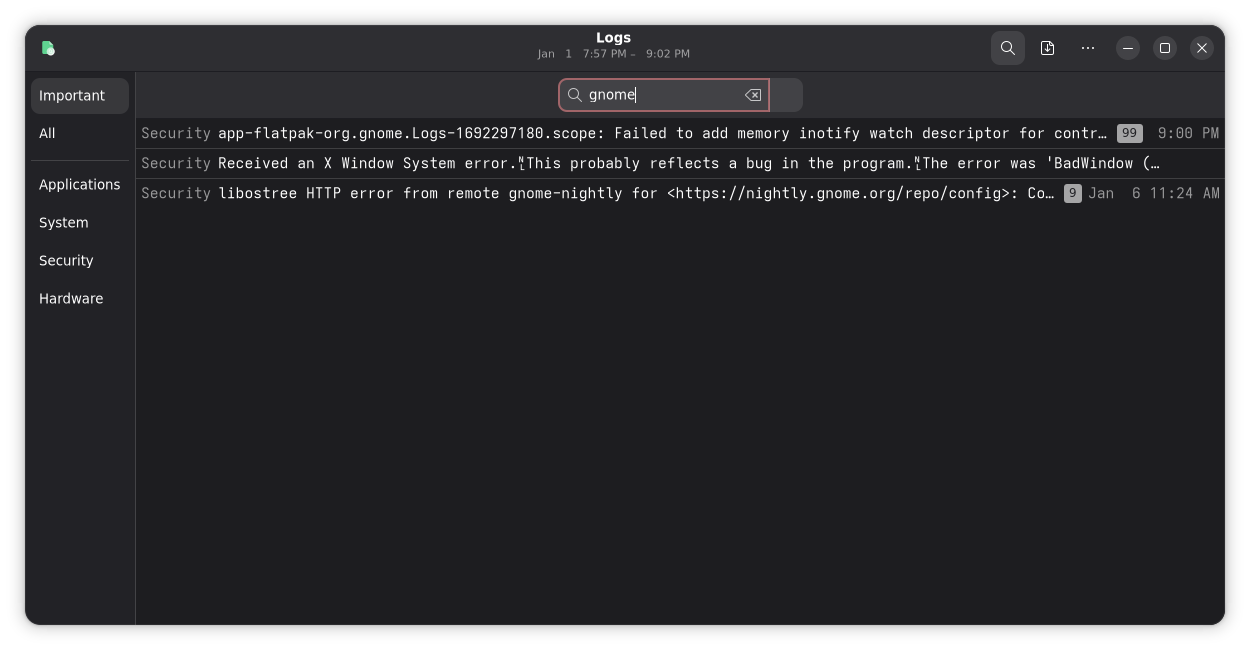

12. Logs & System Troubleshooting

Checking system logs has historically meant running tail or cat against the system log, and these days often means running journalctl, all of which are fine, but can be a bit cumbersome at times when you want to scroll comfortably and figure things out in a more familiar interface. Of course you can also use grep and limit output to just what you want, but either way, it's often lot of scrolling through text that’s not welcoming if you're uncomfortable with the terminal.

But now, you can browse logs in a GUI, filter by time/service, and quickly see failure points without learning commands. CLI solutions are still there, of course, but you not longer need to rely on them for troubleshooting or getting the info you need when getting help from someone else. You can even export your logs to a file with some tools, meaning you no longer have to dig through commands until you get it right.

Log viewers and troubleshooting tools:

- GNOME Logs: A powerful tool for viewing and downloading system logs

- KSystemLog: KDE's solution for viewing system logs

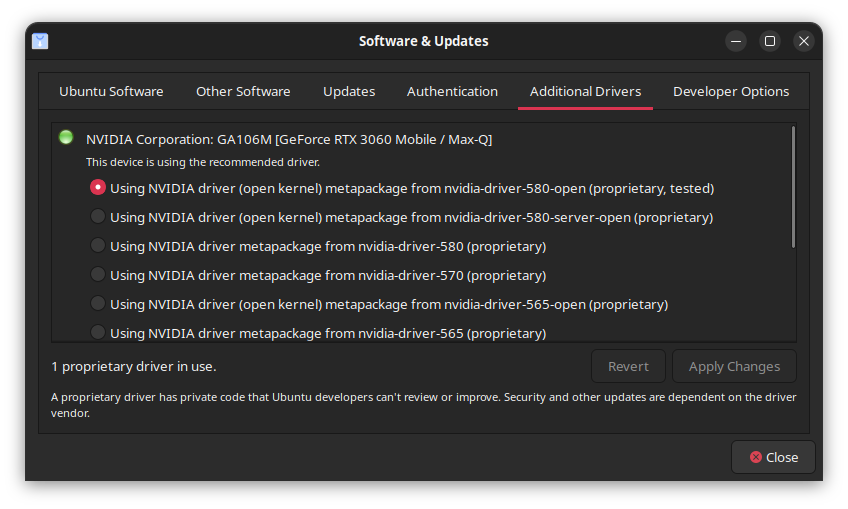

13. Graphics Driver Configuration

As with display configuration, Linux graphics drivers hold a painful place in history for anyone who's been using Linux for long enough. Even till this day, the stigma remains, and with good reason. However, what's no longer true, is that you need the terminal to set them up. It used to be that there was essentially no choice but to open a terminal or TTY, execute a .run file or install a package for your specific distro, and hope that everything works after you reboot.

However, most on most modern Linux distros, you no longer need the terminal for graphics drivers at all. Open-source drivers for AMD and Intel systems tend to work out the box, even for full-fledged 3D acceleration, and Nvidia drivers are quickly closing the gap. Furthermore, most systems provide a smooth graphical pathway for enabling and managing proprietary drivers.

Common GUI approaches (depending on distro/GPU):

- Distro driver utilities: Many distros come with “Additional Drivers/Driver Manager” tools

- Vendor control panels when available: For instance, Nvidia Settings, which comes with the official Nvidia driver

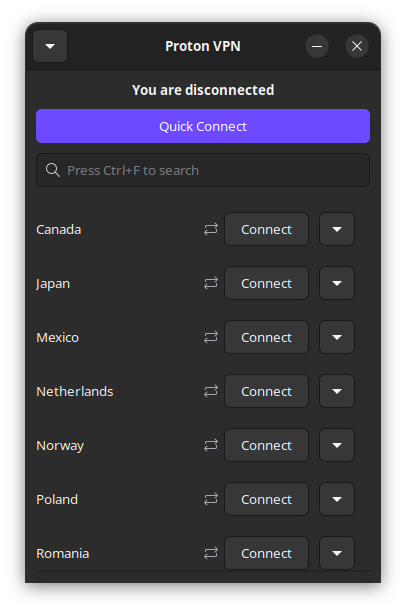

14. Using VPNs

While many servers (including VPN services) run on Linux, the experience on the desktop is another areas where Linux was often left behind. Even popular services would often require you to download and install a terminal-only app and memorize commands just to connect to the service.

Today, many VPN providers provide their own GUI tools connecting to their services. Furthermore, with NetworkManager, it's also possible to set up some VPN services directly through your system settings, much like how you'd set up your Wi-Fi: add a connection, import a profile, connect. It's so smooth and common-place, most users switching to Linux today won't ever know a world where this isn't the way.

Easy GUI VPN setup options:

- GNOME/KDE/etc: Network settings (via NetworkManager), to import profiles (OpenVPN, WireGuard configs, etc.)

- VPN Service Providers: Most provide their own GUI apps

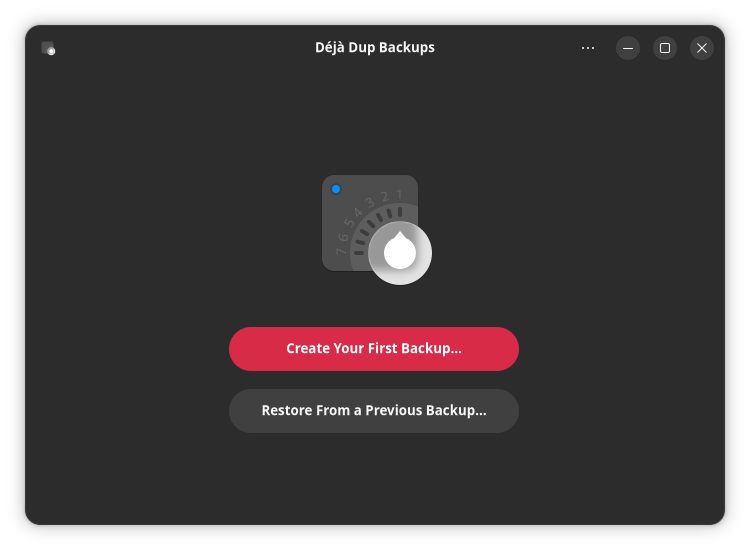

15. Backups and System Snapshots

Backups used to be a mix of scripts, manual copying, and crossed fingers. Now you can do it properly with a GUI and set it on autopilot.

For personal file backups, you can schedule them and restore files easily. For system snapshots (the “I broke something, rewind time” problem), snapshot tools are common and surprisingly approachable.

Everyday backup/snapshot tools:

- Déjà Dup: simple, scheduled backups with a friendly UI

- Timeshift: system snapshots, especially popular on Ubuntu-based systems

- Kup: A friendly backup option for the KDE Plasma ecosystem. Integrates with the system setttings

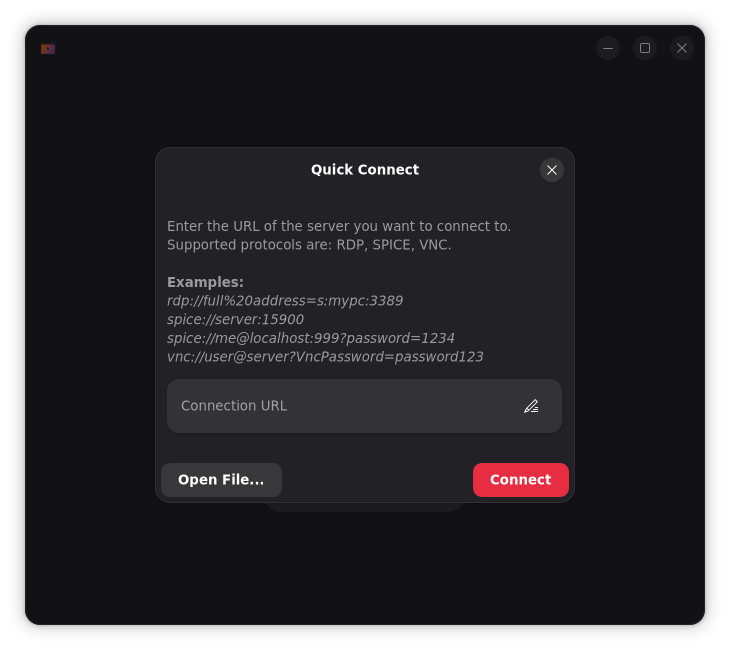

16. Remote Desktop, Screen Sharing, SSH

Remote access is an area where the idea of the terminal being required still persists, though Linux has had robust GUI solutions for quite some time. To be fair, this perception doesn't come out of nowhere. There was a time when remote connections from and to a Linux desktop were a bit of a hassle without the terminal, or a hefty knowledge of the underlying tech.

Plus, SSH connections have a rightful reputation of being CLI focused, because most server work is done through the terminal to save resources. This is quite ironic though, because the X Window System was built with networking in mind.

But the reality is, desktop Linux has long had GUI support for remote access, including SSH, as well as hybrid solutions that combine the CLI and GUI in one interface. So, whether you’re helping someone troubleshoot, accessing another machine on your network, or using RDP and VNC, you can do it with mature desktop apps.

Remote desktop tools that feel like normal apps:

- Remmina: RDP, VNC, SSH, and more in one place

- Field Monitor: RDP, VNC, and SPICE, especially geared for VM management

- Virt Viewer: VNC and SPICE viewer for VM consoles and remote displays

- KRDC: KDE’s RDP and VNC client

- GNOME Connections: a simple remote desktop client for RDP and VNC

Final Thoughts

The Linux terminal isn't going anywhere - it's still central to everything we experience today. It's faster for some workflows, easier to document in guides and forums, and often the most portable way to explain fixes across distros. While you don't need to be afraid of the terminal, the idea that you can't experience Linux without depending on the terminal is quickly becoming a myth of the past.

It's not that Linux became “GUI only”, but that the Linux desktop has become far more complete. The modern desktop we know today ships graphical tools that cover almost every common task in ways that are genuinely approachable, so the where reputation lags behind reality, it's mostly because old advice sticks around, and because it's convenient to default to command snippets to save time.

If you're new to Linux, or you are returning after a long time away, now's a good time to clear whatever notion you may have had about the need to use the terminal. It's still there, and probably always will be, but it's no longer the defacto experience on Linux in 2026.