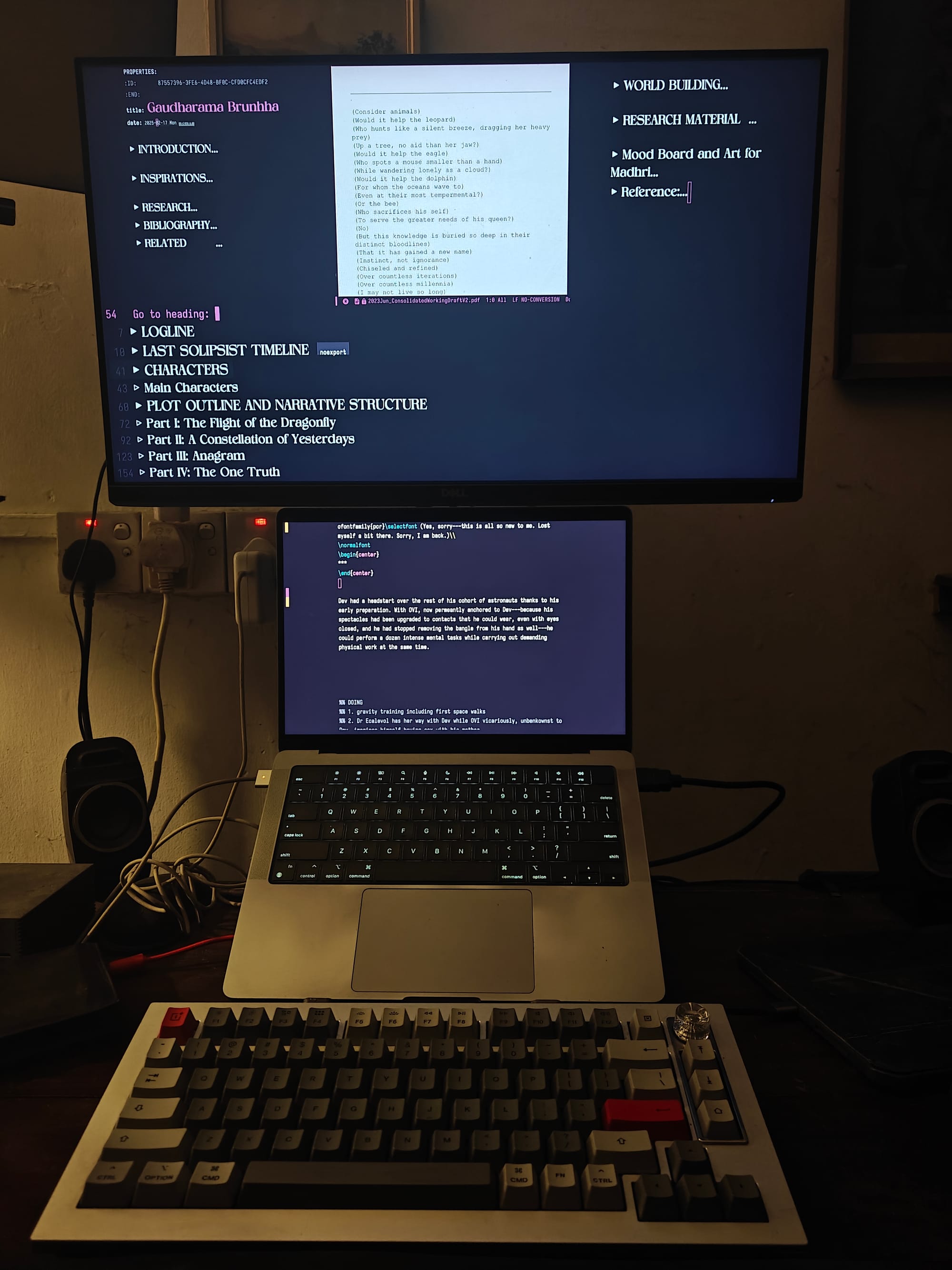

The author working on his manuscript. The screen is divided between the LaTeX manuscript, its PDF, and the notes in org-mode. © Theena Kumargurunathan, 2026

In Part I of this article, I alluded to how Emacs' UX has allowed me to create a writing workflow to fit the way I think, write, edit and worldbuild.

But Emacs is more than my tool for thinking and writing: it is also direct inspiration for a Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) for my next science fiction novel. Much of the dramatic extrapolations for this BCI came from experience: imaginative extrapolation is easy when the tool itself feels both timeless and futuristic.

In part II, I want to use a different route.

I will start by tracing a brief historical outline of the philosophical and design choices that has made Emacs a veritable digital habitat for writers like me. In doing so, I've made an effort to ensure that the presentation isn't overly technical---this is in consideration of the fact that both the writer of this piece, and its primary intended audience, are both non-programmers.

I will then demonstrate how these decisions directly affect my writing workflow over its different phases.

A Brief History of the Future

Good UX comes from good design. The former is the harvest that comes about from sowing in the latter.

Emacs feels timeless to me because it made a simple, stubborn choice early on: let the user shape the tool. Consequently, Emacs users treat the editor less like an app and more like a modular Swiss army knife that invites the user to mould it for any text-centric work.

This is no accident: Emacs has always given priority to user agency. At the risk of repetition: that stance matters now during the age of AI where big tech is throwing AI into everything (Microsoft will be updating its venerable Notepad with AI---let that sink in).

Emacs provides building blocks that are plain and durable because it centers everything on text: buffers are workspaces, not just files; modes give those spaces a purpose, while small add‑ons layer in habits writers care about: word counts, spell checks, captures, exports. You don’t have to learn a new app to switch tasks.

My experience is usually along the lines of I wonder if I can do this on Emacs, and the answer is usually a resounding yes.

Emacs also grew carefully, not fashionably. It started on terminals and added a GUI without losing its clarity or diluting its user-centricity. Performance improved step by step, but never at the cost of readability. Support for global writing—Unicode, font choices, clean rendering—arrived without breaking the rhythm seasoned users rely on.

This doesn't mean that Emacs is somehow impervious to change. Emacs absorbs new technology by translation, not reinvention. When the world moved to version control, Emacs welcomed it through text and simple interfaces like Magit; what started out as a simple outliner has grown into Emacs' killer feature.

The result of all this malleability is that Emacs is at once my hypertextual ideas and research storage, my studio for brainstorming, and my workshop for crafting the written word.

Emacs as Hypertextual Ideas and Storage

Back when I was writing and notetaking on a word processor like some neanderthal, I would connect distinct word files and sections within these files using MS Word's hyperlinking function. This allowed me to link files and mimic the hypertextuality of the web.

This was all well and good until I had dozens of Word documents open. Finding the right one in a cascade of windows was annoying, but the bigger issue was how slow the entire experience would become.

Emacs solves this beautifully using Org-Roam and Hyperbole. The former requires unique file IDs in order to create a mini-database of connected nodes---the same functionality that Notion and Obsidian offer.

Org-Roam has become my second brain. Explaining its functionality will require a separate article. In short, it is my personal knowledge management system, the bucket that I vomit ideas into. This vomit-box of ideas are available at a moment's notice. Once the idea begins to take shape, I refine these notes over time, creating change-logs, connections to related notes, etc. Once the research phase begins, Emacs' built-in support for Bibtex lets me cite my research.

Hyperbole takes a different approach: it allows you to link to files no matter where they are located in your system, specific line numbers in files, create implicit buttons, and automate all these actions in one go. It doesn't require databases. I've only recently started experimenting with it, and so far have been blown away.

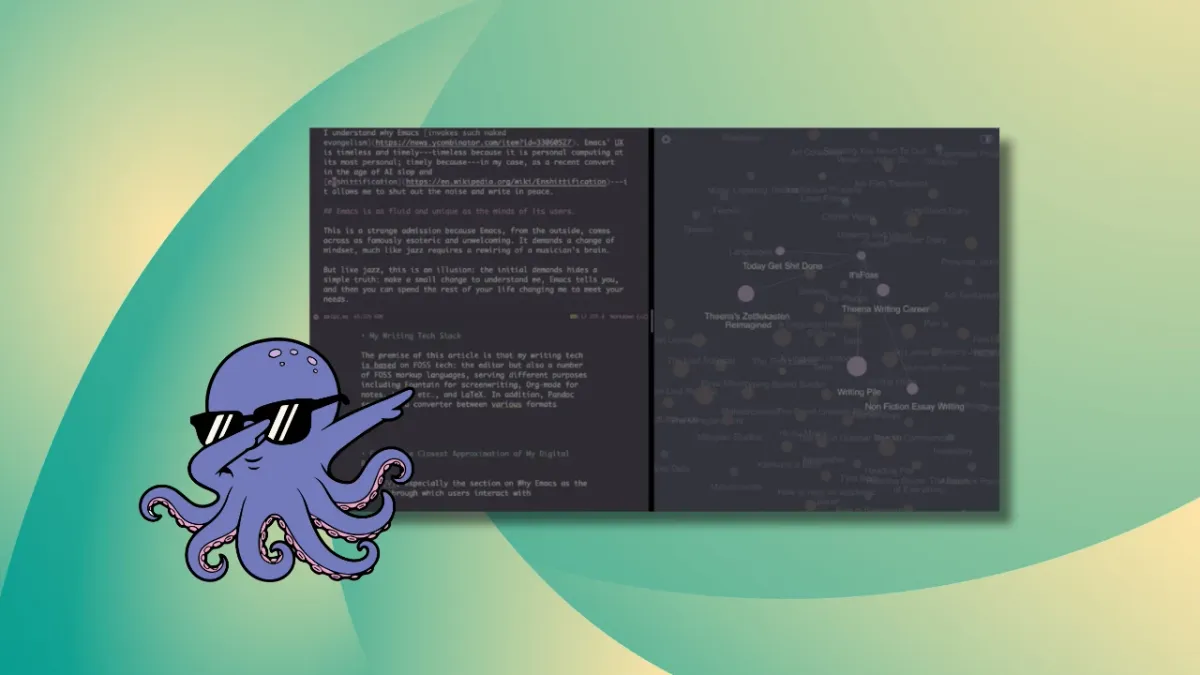

The author's note-taking workflow with Org-Roam © Theena Kumargurunathan, 2026

Emacs as Workshop for the Written Word

I am a novelist and a filmmaker. From a workflow standpoint, that means I work heavily with two file-types (or modes in Emacs-speak): LaTeX (for my manuscripts) and Fountain (for screenplays). There is not a single writing environment that can support long-form writing and screenwriting. Combine that with its support for note-taking, personal knowledge management, and task management, and you begin to see why Emacs illicits such a strong emotional and cognitive pull. It isn't merely the writing studio I've always wanted; it is an environment for thinking and making.

- Overleaf

- Final Draft

FOSS software to pair it with:

- Skim/Zathura PDF readers

- Storyboarder

Emacs in the Age of Enshittification

The era of enshittification is upon us. The age of AI is also upon us. These tools seem to suggest that those of us who have spent decades honing our individual craft have wasted our time: let me write that story you are struggling with, let me create the visuals that you are working on, let me vibe-code that idea for an app.

Now, more than ever, user agency should be the primary concern of users. Realistically, gaining complete user agency is beyond the majority of users: on phones, on laptops, on tablets most users are happy, most of the time blissfully unaware of the hidden costs---financial or otherwise---of giving up on user agency.

Now, more than ever, user agency should be at a premium---especially for creators of all sorts. As a novelist, I've made the decision: this is my life's work, and I will not trust big tech with it.

Emacs is many things to me.

It is my vomit bucket for ideas.

It is my research library for refining ideas.

It is my workshop for honing stories, for page and screen.

Most of all Emacs is, in the age of slop, my digital oasis.