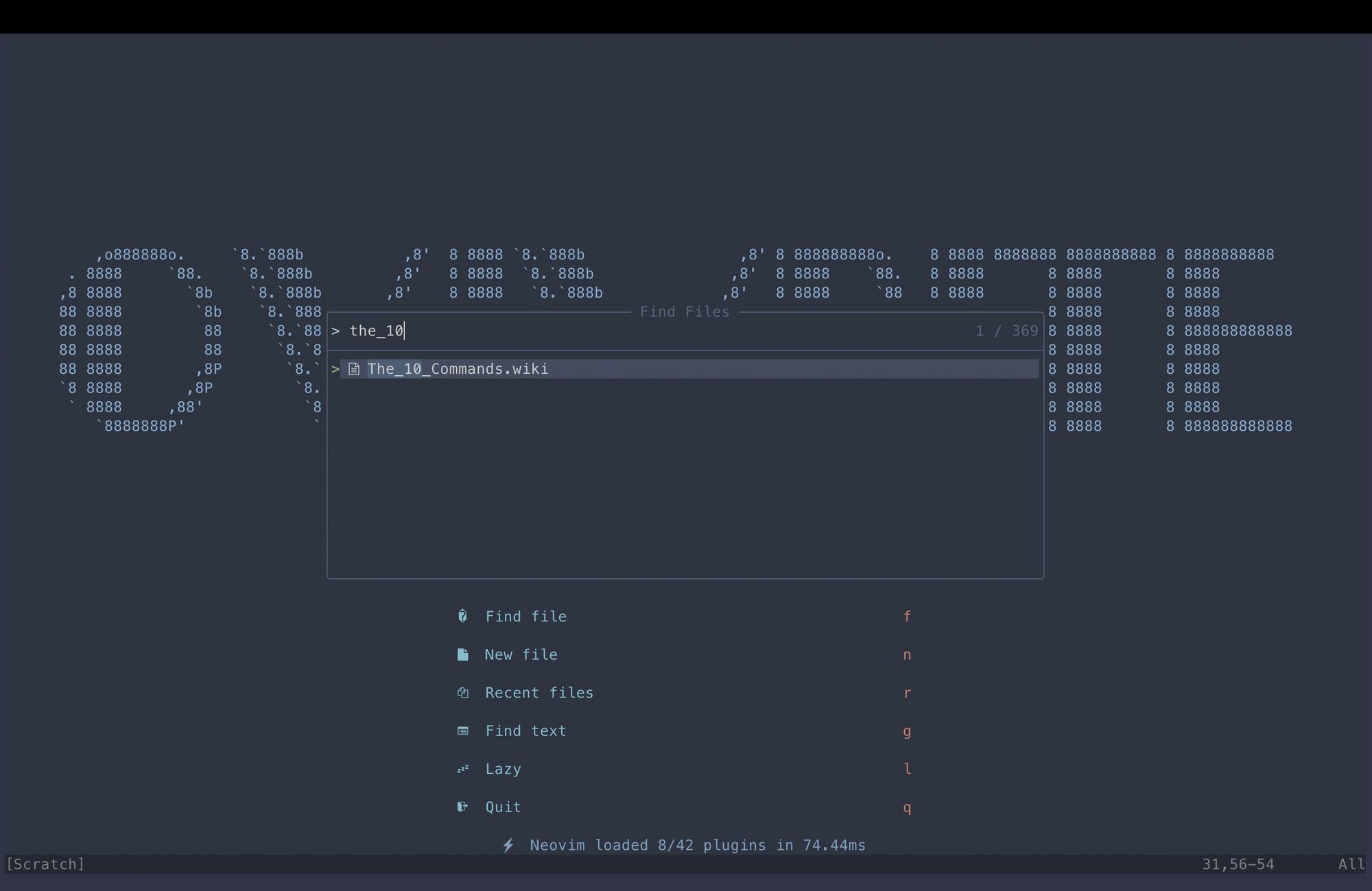

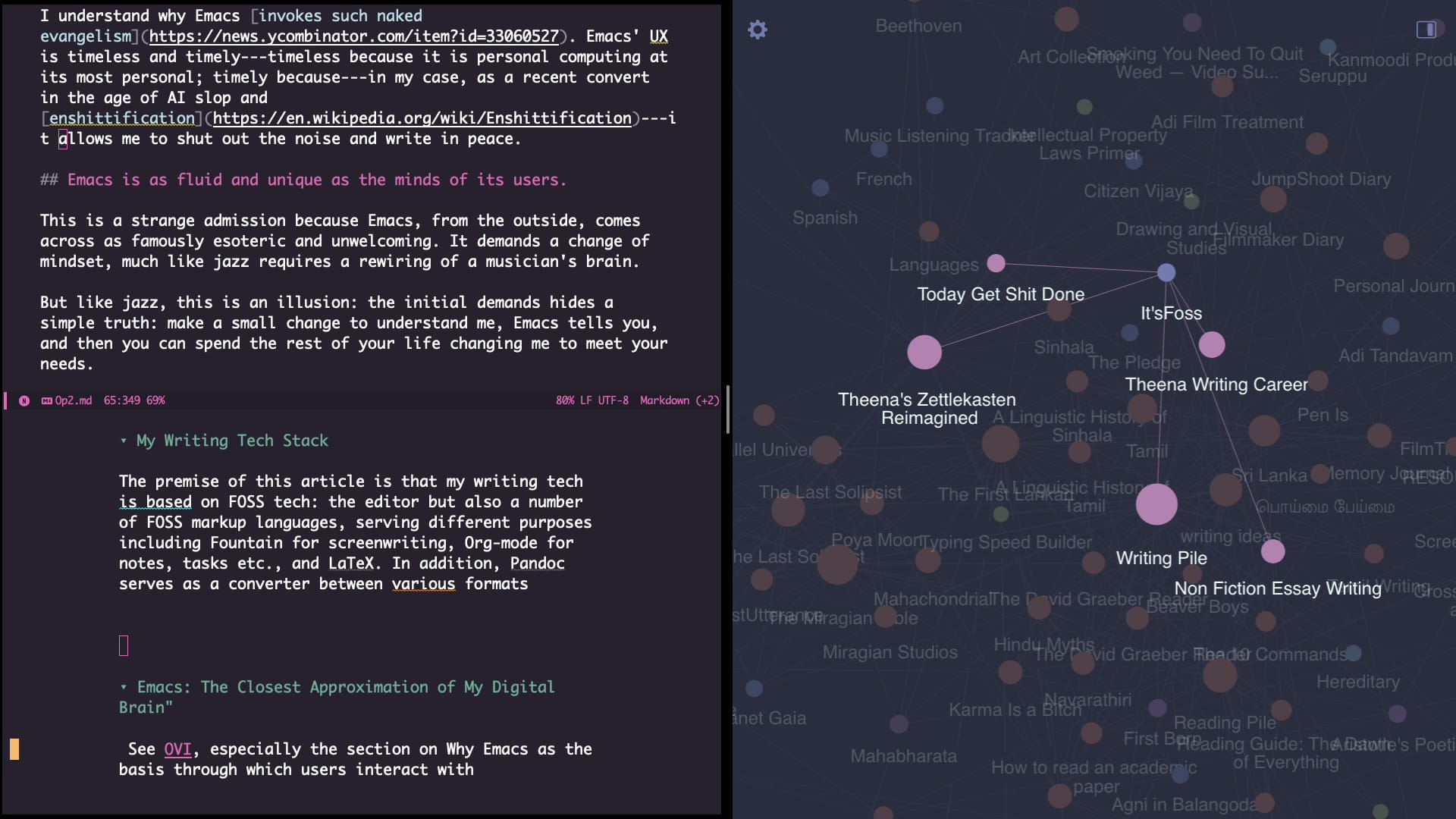

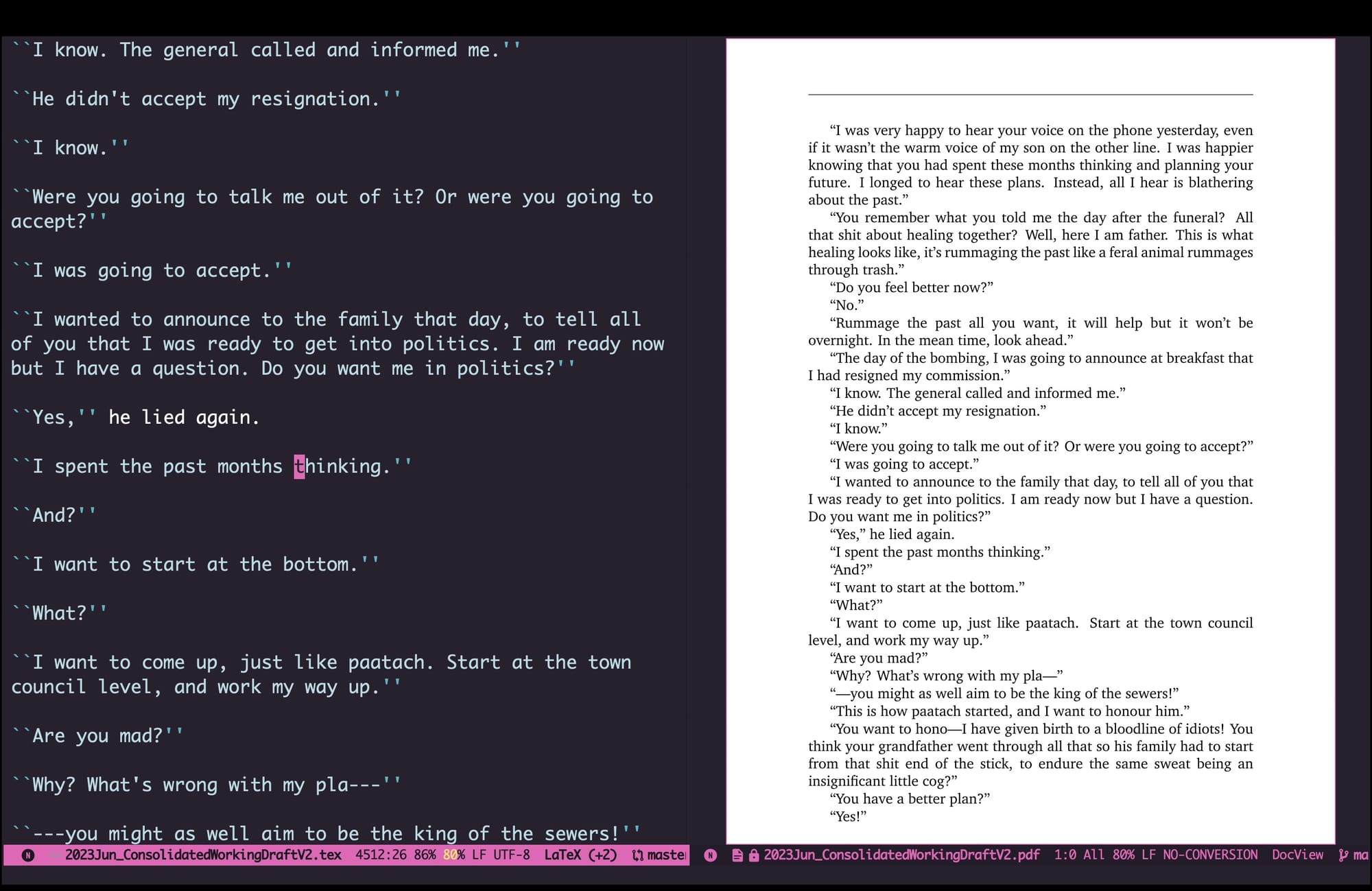

The author's Emacs environment © Theena Kumaragurunathan

My next novel, a science fiction story set 500 years in the future, features a sentient artificial being---imagine a HAL 9000 with a functioning moral compass, or Skynet without the genocidal nihilism.

Users interact with this sentient AI being in a variety of ways: non-tech users interact via voice commands and touch, but more tech-savvy users interact through a Brain-computer Interface (BCI) that enables tactile and vision control. A smaller portion of users still use keyboards, but they are viewed in the same way our current age views typewriters: a quaint artifact of a bygone era.

I've been working on this novel since 2013 and one of the most difficult parts of the writing was imagining this BCI. It had to be futuristic but still grounded in technology—not magic. I imagined this BCI to the AI being would be malleable in a way that the software of today generally isn't. I envisioned it would be programmable, that it would come with some sort of scripting language that would allow for the user to continue honing the BCI.

Of course, back in 2013 when I began working on the novel, I was writing on word processor like most of my contemporaries. This wouldn't change until 2020, when the pandemic hit.

Vim in the time of Corona

I've already written about my pandemic fling with Vim . To call it a fling is doing Vim/Neovim a disservice: between early 2020 and 2023, Vim (and later Neovim) had convinced me to leave word processors (and proprietary formats) for good.

During this period, I moved all my writing away from *.doc file format to *.md and eventually *.tex; I moved my research notes (that had been in *.txt files accessible via Windows Notepad) to *.org; I presented my workflow at the annual Neovim conference three times during this period, spanning non-programmer topics like Writing, Editing and World-building at the Speed of Thought on Vim, and Vimkipedia: Or How I Built My Second Brain on Vim .

I even spent a year during this period working on a Integrated Writing Environment (IWE) based on Neovim's Lazyvim framework which I called OVIWrite (as in Oh We Write).

OVIWrite was a pet project, made with the kind of naivety that newcomers have when learning a craft; here I was, a novelist who had dropped out of computer science two decades earlier because he couldn't code, using a programming language and tools to help create the writing tool I had always wanted. It was ridiculous and shouldn't have worked.

But it did.

For close to a year, my novel was crafted within this IWE. During that period, much to my shock, I found OVIWrite gaining a user base: there are now close to a dozen users, some of whom, like me hobbyist programmers coming from a variety of non-programming background (I count among its users a lawyer, a philosopher, and a biologist), who use it to get their prose, mostly academic writing, done. Until six months ago, I was merging pull requests and helping some of these users with technical support over email.

It's one of the more unexpected and satisfying detours of my life—if I could go back in time and tell the 20-year-old me who dropped out of undergrad computer science, distraught at being told he wasn't smart enough to be a programmer, he would be utterly confused.

So why then did I turn my back to (Neo)Vim and head towards the land of Emacs?

Oh We (Should Be) Writing, Dude

As much fun as it was to wrangle Neovim to become a one-stop tool for all my writing needs, I had to face up to a growing realization: all the constant tinkering and tech support (for myself and tiny band of users) was keeping me away from actual writing, and completing of my novel. You know what they say, keep the main thing the main thing?

Ten years had flown by, and the novel was only around 60% complete. While the Vim and Neovim ecosystems had tools for writers and writing, most of these were either primitive or required constant tinkering to get them to work for me.

Orchestrating between plugins written in Vimscript that hadn't been updated in years, neovim plugins written in Lua that were fresh out of the oven, a smorgasbord of plugin managers old and new, and LSP configurations for prose, took time. I am sure if I was a proper programmer, this wouldn't have been the case, but I am not; documentation that would take normal programmer types half a day to understand, would take me days.

The Lightbulb Moment

You will wonder why I didn't go to Emacs in the first place. Reader, I tried.

While Vim's keybindings seemed almost natural (it annoys me that modal editing isn't known outside of programming circles), Emacs' keybinding was akin to playing jazz piano.

All that changed last year: I had several light bulb moments with Emacs within a week.

- With Evil, I could bring the best part of Vim into Emacs: its modal editing

- While there were Emacs distros that existed (Doom Emacs, SpaceMacs), all with support for Evil keybindings, their modular config files were confusing. Rahul M. Juliato solved this problem by creating a kickstarer pack for Neovim migrants, focusing on Evil keybindings and a single config file

- I realized elisp was easier to read (and write) than Lua

- The dreaded Emacs pinky finger problem could be solved easily with a keyboard configuration tool

On Oct 15th 2024, I wrote the following on my personal journal:

"I think I am finally cracking the mysteries of Emacs"

Suddenly, I saw the full glory of Org-mode, Org-Agenda, and Org-Roam. I tried replicating my OVIWrite config on Emacs—it took barely an hour and everything was up and running—and it had PDF and Ebook readers, a built-in browser!

Emacs had an extensive eco-system for writers that had been continuously refined and tested over years. And unlike Vim/Neovim, there was already an emacs config for pure writing. On Oct 16th, I opened my manuscript (in LaTeX) via my brand new Emacs config.

One Year Later

I understand why Emacs invokes such naked evangelism. Emacs' UX is timeless and timely---timeless because it is personal computing at its most personal; timely because---in my case, as a recent convert in the age of AI slop and enshittification---it allows me to shut out the noise and write in peace.

Emacs is as fluid and unique as the minds of its users.

This is a strange admission because Emacs, from the outside, comes across as famously esoteric and unwelcoming. It demands a change of mindset, much like jazz requires a rewiring of a musician's brain.

But like jazz, this is an illusion: the initial demands hides a simple truth: make a small change to understand me, Emacs tells you, and then you can spend the rest of your life changing me to meet your needs.

Fiction Begat Life Begat Fiction

Which brings me to my fictional world's BCI.

This interface to a godlike AI is very much inspired by Emacs.

This neural Emacs retains the core user experience of Emacs we know today: it is extensible, malleable, and self-documenting software.

Since the keyboard is now a curious artifact of times past, cultures in this world have replaced keyboard bindings and keystrokes to thought patterns or neural gestures: instead of pressing C-x C-f to find a file, character's brain fires the neural pattern to represent the gesture I want to find something, leading to a mini-buffer in mind's eye of the user. Fuzzy file finding and even suggestions would appear in this neural interface.

Kill-rings (system clipboards for you non-emacs users) and registers are incredibly powerful: my characters maintain multiple streams of conscious thought simultaneously in distinct buffers. The kill-ring isn't just storing thought; instead it becomes a rich repository of my characters' thoughts that they can recall and manipulate at any time.

My fictional version of elisp, which I call OVIlisp also benefits from this evolutionary leap. It is a programming language for manipulating thought patterns directly: not only can my characters write functions to transform text but they can also shape how thoughts are captured and expressed.

The Emacs doctor function evolves into a personal, on-demand therapist.

Emacs Frames and Windows map to different zones of conscious attention. Users could partition mental workspaces into regions dedicated to different tasks.

Org-Roam's concept of backlinks would become something far more profound - not just links between notes, but links between thought patterns themselves, resulting in something called "neural knowledge graphs" where each node isn't just a note, but a complete thought pattern that can be recalled and re-experienced. In my fictional world, version control of thought patterns is as normal as TODO lists is in ours.

This isn't magic.

It's an extrapolation of how I work today.

In part 2 of this article, I will go into my Emacs workflow, focusing on the tech stack that enables me to write novels, research notes, film scripts, and yes code, in a single environment.