In the Linux world, there are a few primary giants that most other distros have historically been built on and one of the chief among these is Debian. Giants like this may not be quite "household names" outside our (rapidly growing) sphere, but they're among the wise council of elders that most of us are familiar with.

Speaking of Debian, you've probably heard by now, it's "The universal operating system". That's an official Debian tagline, and you may have seen it in memes or elsewhere across the web.

With just how many distributions are based on Debian, you might have taken a guess as to why. But what does this really mean, and why is it still said today? In this article, we'll take a peek into the history of this tagline, and what it means in reality. Plus, I'll answer the question: Does Debian actually live up to this claim?

History: Why Debian Aimed to Run Everywhere

To get an idea of where this idea comes from, we need to have a quick look into Debian's history and purpose.

As mentioned earlier, the most important detail here is that this isn't a community-driven saying, but part of Debian's own official branding, and it's been a part of its identity for a long time.

Debian came into existence early in the Linux timeline. Ian Murdock founded the project in 1993, with the intent of building a distribution openly, in the spirit of Linux and the GNU project. The emphasis from the beginning was for Debian to be carefully maintained and supported, rather than being a haphazard collection of parts or casually abandoned. This motivation is declared even in the Debian Manifesto.

Porting as a Culture

It's worth noting that Linux itself was ported to other platforms early on, so it makes sense that Debian's universal mindset likewise developed early in its life cycle, with a flexible approach to hardware. While some of the more popular operating systems of its time (DOS, Windows, and OS/2) were primarily focused on the x86 PC as a target platform, Debian wasn't afraid to spread a wide tent.

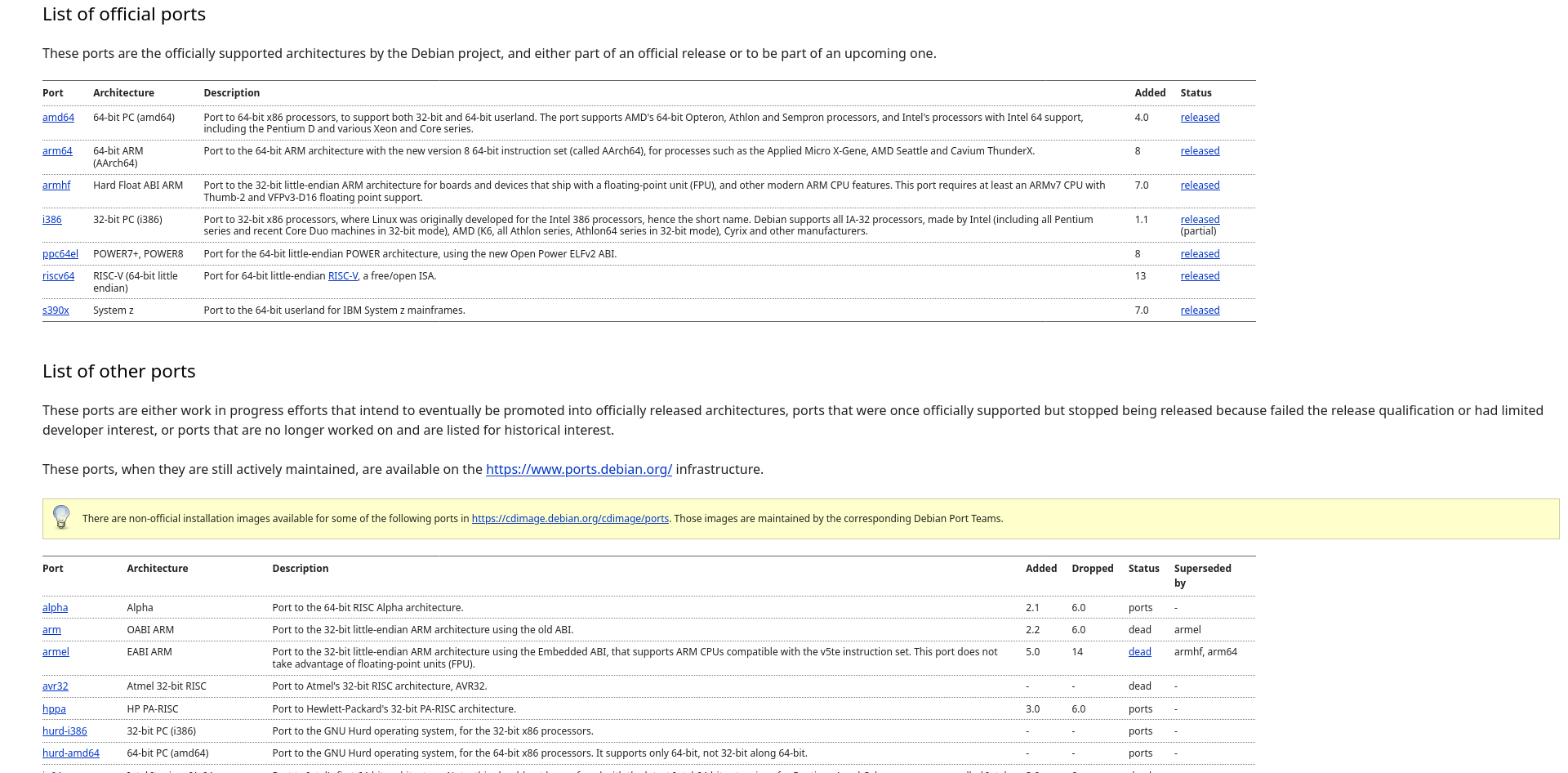

Porting Debian became part of Debian's culture early on, with the first porting work beginning in August 1995 to the m68k instruction set. Later, Debian was ported to other platforms, including PowerPC, MIPS, SPARC, and other RISC-style architectures. This mattered at the time, because these platforms weren’t mere curiosities, but the heart of real workstations and servers used across various industries. In other words, Debian hasn't pursued a universal image for the sake of marketing; it's been a part of the Debian culture since almost the beginning.

A True "Linux For Everyone"

Even from early days, Debian has presented itself as broadly usable for everyone, and it still frames itself that way today. Where other major legacy distros, like Red Hat, Gentoo, and Slackware tended to focus on serving specific audiences, Debian remained the domain of users who want their system to be dependable and predictable.

Debian's porting efforts are therefore critical to its goal: to be a community project for broad, general-purpose usability across many kinds of machines.

Has Debian Stayed True To This Slogan?

In many ways, yes: Debian is still a very "universal" operating system. It still has broad support for a number of architectures, and still ships tens of thousands of packages for them. Debian 13 (Trixie) also officially supports the emergent riscv64 architecture, which shows that the project continues to pursue new platforms as they come into relevance. However, in some ways, Debian's universal scope is narrowing, and that is arguably a reasonable trade-off.

That said, it's important to understand why this is. It's not that the goal of Debian has changed, but rather the combination of the computing landscape changing over time, and the reality that, like many open-source projects, Debian still depends heavily on volunteer developers.

Universality is a Monumental Effort

Even with a vibrant community and support from corporate stakeholders, keeping legacy systems alive indefinitely is not something Debian can realistically promise, especially as upstream projects stop supporting older targets. For example, Debian dropped i386 as a regular architecture as of Debian 13 (Trixie), keeping only legacy support for running 32-bit code on amd64 via multiarch and chroots. This means there is no official kernel and no Debian installer for i386 systems, and users running i386 systems are advised not to upgrade to Trixie.

Trixie is also the last release for armel, in the practical sense that it is no longer supported as a regular architecture. Upgrades are possible for certain hardware (or with third-party kernels), but it is expected to be removed in a future release.

These Are Totally Fair Choices

Frankly, this should not affect the majority of users, since most mainstream PCs have been on 64-bit x86 for years.

That said, retro-PC enthusiasts (and anyone maintaining older hardware for specific reasons) may have to stick with older Debian releases for full i386 installs, switch to different hardware, or do more hands-on work to keep their preferred setups running.

Why Distros and Hardware Vendors Still Choose Debian (As a Base)

Most of us aren't trying to reinvent the wheel every time we want to do something new. Likewise, distro maintainers and hardware vendors building their own distros for Single Board Computers (SBCs) and other custom hardware don't want to have to start from scratch every time they need a software stack. Debian's predictability and stability offer a solid basis for them to build on, because these qualities are a major part of what makes its universal promise possible.

While Debian has a huge catalogue in its repos, it doesn't chase after the "latest and greatest" of software, because what's latest isn't always what's greatest when the goal is to minimise software faults and present a target that can last for a long time. This is why Debian is the basis for such distros as Raspberry Pi OS (formerly Raspbian), Armbian (Debian-based images for many SBCs), DietPi, and even purpose-built projects like Proxmox VE and Tails, as well as Debian-rooted desktop options like Ubuntu and Linux Mint Debian Edition (LMDE).

Debian also does much of the underlying architectural portability work while keeping the core experience intact, and it has even produced non-Linux ports like Debian GNU/Hurd and, for a time, Debian GNU/kFreeBSD.

The common thread is that Debian provides a slower-moving foundation without compromising on usability, and it balances experimentation where necessary. This lets downstreams keep their focus and energy geared towards the extras, like hardware enablement, sensible defaults, and end-user experience, instead of rebuilding the entire stack.

Final Thoughts

I hope you've enjoyed learning about why Debian is called "the universal operating system." It's more than a fun piece of trivia: it's a deeper concept that underpins the very nature of Debian as a project.

Debian has earned this label through a consistent mindset and follow-through, with a commitment to broad usability, a culture of portability, and an approach to stability that makes for a dependable base for everything from desktops and servers to downstream distributions and specialised hardware.

While Debian’s scope has narrowed in a few places as the industry evolved, it hasn't retreated from this core ideal. It’s a realistic way of keeping the promise alive and meaningful, so Debian can truly remain "the universal operating system".